On the Recent Cool Temperatures in WA State

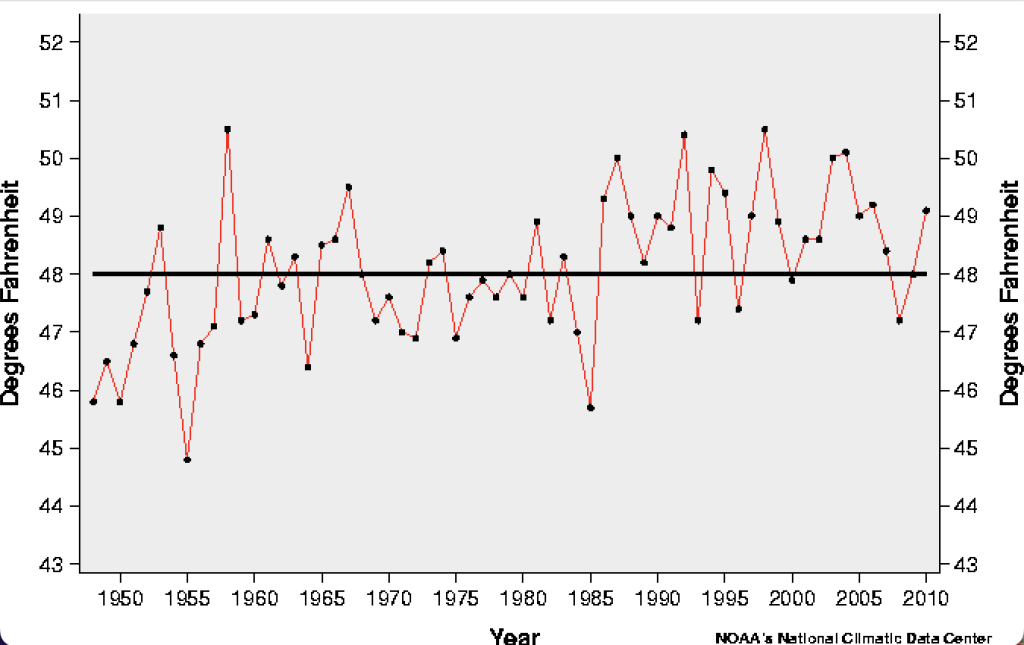

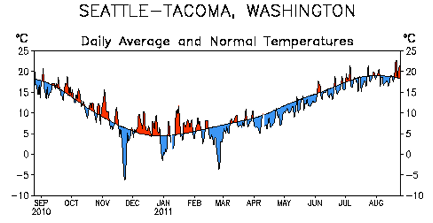

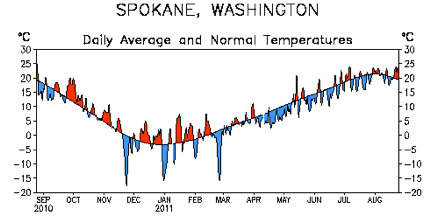

It is widely appreciated that relatively cool weather has plagued, or blessed, depending on your point of view, Washington State since the end of February 2011 as illustrated in the temperature time series for Seattle and Spokane (Figure 1). According to climate division data from the National Climatic Data Center (NCDC), the mean statewide temperature for April through July 2011 (53.2°F) was the second coldest in a record extending back to 1895. This spell of below normal temperatures is on the heels of a cool spring and summer in 2010, and in 2008. While recent temperature anomalies have been especially prominent in spring, they are not restricted to that season. Annual average temperatures during the last few years have been colder than typical of the last few decades (Figure 2). The objective here is to provide perspective on this unusual, and perhaps puzzling, aspect of our climate of the last few years.

First and foremost, it is important to recognize that the climate is far from static. Just like the weather varies from day to day, the climate fluctuates on time scales ranging from years to decades. These fluctuations are largely intrinsic. In other words, the climate is a chaotic system, and its internal workings can bring about remarkably persistent deviations from long-term (multi-decadal) averages. Our ability to predict these swings is minimal. The state of the tropical Pacific atmosphere-ocean system, specifically El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), has systematic influences on the seasonal mean weather in many parts of the world including the Pacific Northwest, and we now have some skill in predicting ENSO on time horizons of 6-12 months. But aside from ENSO, there is very little for us to hang our hats on, again because the climate system makes its own deviations out of thin air (pun intended). It has been pointed out that interannual variations in the temperature and precipitation in the Pacific Northwest correspond with variations in the leading pattern of North Pacific sea surface temperatures, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO). Nevertheless, this does not imply that the PDO is necessarily a useful predictor of our weather. To a large extent the PDO merely reflects the ocean’s response to the weather that has occurred – just as a conference championship is a result rather than a cause of a team winning more of their games. The situation is not completely hopeless in that the atmosphere appears to have some sensitivity to slow-evolving surface conditions outside of the tropical Pacific, i.e., sea surface temperature, soil moisture, and snow and ice cover anomalies. Information on these anomalies is being used in seasonal weather prediction, and there is a substantial ongoing effort to derive as much as possible from these sources of predictability. The limitations here are illustrated by the present example; there was no indication during the middle 2000s that it would turn cooler. The bottom line is that the climate has plenty of tricks up its sleeve, and simply it should not be much of a surprise when the weather becomes weird.

The fluctuations in the climate can serve to obscure long-term trends, especially in places like the Pacific Northwest for which the magnitudes of these trends are modest. Readers are encouraged to explore this for themselves using an application on the OWSC website (http://www.climate.washington.edu/trendanalysis/). This user-friendly interface allows one to quickly assess mean trends in temperature, precipitation and snowpack for different times of year and intervals and to plot time series from individual stations. It is striking how sensitive trends are to the years that are used for the endpoints of a record. This issue is by no means trivial. It would be very useful for planning purposes to know when global climate change is liable to overwhelm the climate variability or “noise”. Since we cannot anticipate these variations, especially on a regional basis, estimates of a time scale for climate change are necessarily tentative, and in broad terms.