Early Fall Storms in the PNW and their Connection to Western North Pacific Typhoons

This month marks the 50th anniversary of the Columbus Day storm, by many measures the strongest extratropical storm to hit the lower 48 states in the past century. The Columbus Day storm formed out of the remnants of Typhoon Freda. Similarly, one of the strongest storms in recent memory for Europe was the “Great Storm” of October 1987, which grew out of the remnants of a tropical cyclone in the Atlantic. Forecasters have appreciated that the predictability of the weather for the North Pacific and North America can be compromised by the uncertainty associated with typhoons undergoing extratropical transition in the western Pacific (e.g.,Torn and Hakim 2009). The greatest flooding and wind events in Alaska are often associated with this kind of disturbance. Could the same thing actually be the case for our neck of the woods? This question inspired a look back at other early fall storms, taking advantage of the marvelous resource represented by Wolf Read’s website on past storms in the Pacific Northwest (http://www.climate.washington.edu/stormking/).

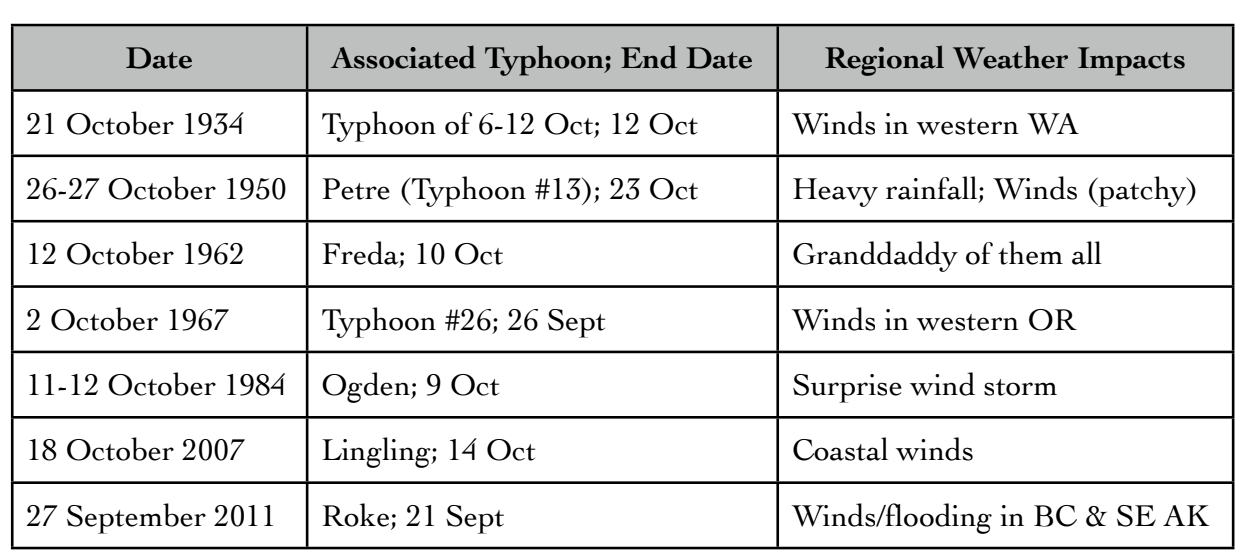

The Storm King website was used to identify the events for analysis. All of the October storms listed were examined; also examined was a notable event that impacted Vancouver Island in October 1984, and a more recent event that occurred in British Columbia and southeast Alaska in late September 2007. This yielded a set of 7 cases (itemized in Table 1), which may be enough to make some tentative statements. The evolution of these events, and in particular their potential connection to tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific, was assessed through inspection of 6-hour composite maps of 500 hPa geopotential height, sea level pressure, and precipitable water from NCEP Reanalysis data sets (available from the following website: http://www.esrl.noaa.gov/psd/data/gridded/reanalysis/). The intent here was not to carry out a diagnostic analysis but rather to simply trace the history of the disturbances that have lashed the Pacific Northwest in early fall.

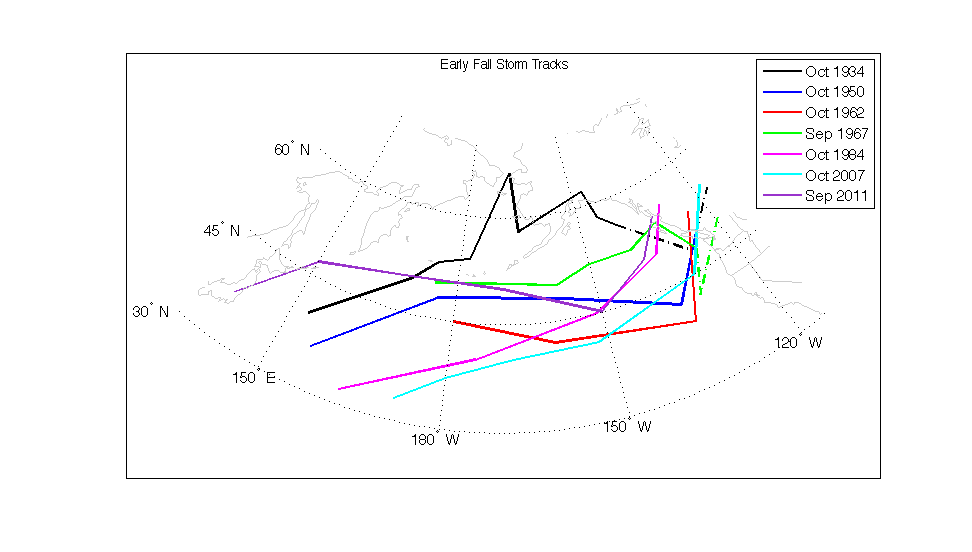

All seven storms that were checked had a connection to a typhoon in the western Pacific, with tracks shown in Figure 1. In two cases this linkage appears to be less than direct. An example here is Oct 1934, during which a west Pacific disturbance, after extratropical transition, underwent considerable change in morphology into a large quasi-stationary low in the Gulf of Alaska. A secondary low that developed to the southeast of that center became our storm. A similar sort of scenario seems to have occurred for the October 1967 case, and these two cases have hatched lines on Figure 1 to represent that. But for the other 5 events, the cyclones appear to have maintained their identities from their tropical phases in the western Pacific, through their transitions to extratropical lows, to making landfall in the Pacific Northwest. It should be emphasized that these disturbances were not strong during their entire trip across the Pacific. Instead, as discussed by Wolf Read and others, (e.g., Reed and Albright 1986; Mass and Dotson, 2010), powerful storms in the Pacific Northwest typically undergo a stage of intensification shortly before landfall.

The point we wish to make here is that the tropical origins for our early fall storms may be more common than previously appreciated. This finding raises a couple of questions. The western North Pacific is a hotbed for tropical cyclones, and plenty of them recurve into the westerlies. So what is special about the few that survive the trek across the Pacific? In addition, the tropical cyclone season in the west Pacific usually lasts into November, as the mid-latitude storm track is really cranking up. Do our November storms also frequently have connections to west Pacific typhoons or are there factors, perhaps associated with the background flow, that work against it? As a bit of an aside, the storm of 2 November 1958 was also examined, since it was rather early in the season, and because of Wolf Read’s analysis, which indicated it had signatures of a warm-core tropical storm system. The interesting result here is that it was the only case examined that appeared to lack a linkage to a west Pacific typhoon. The bottom line is that we think our results are intriguing but emphasize they are also tentative. It does motivate keeping an eye on what is happening west of the dateline.