Early Autumn Fog in WA

Fog may not seem that dramatic of an element of the weather, but it can actually be a big deal and certainly represent a challenge for forecasters. An obvious impact of fog is on aircraft operations. Thick fog can hamper takeoffs and landings, as well as cause delays on the taxiways. Fog has also been implicated in a number of vessel collisions on the waters of Puget Sound. Examples of these during the early fall include the sinking of the Multnomah after being rammed by the Iroquois in 1911 and a collision between two Washington state ferries, the Sealth and Kitsap, in fog with relatively minor damage in 1991.

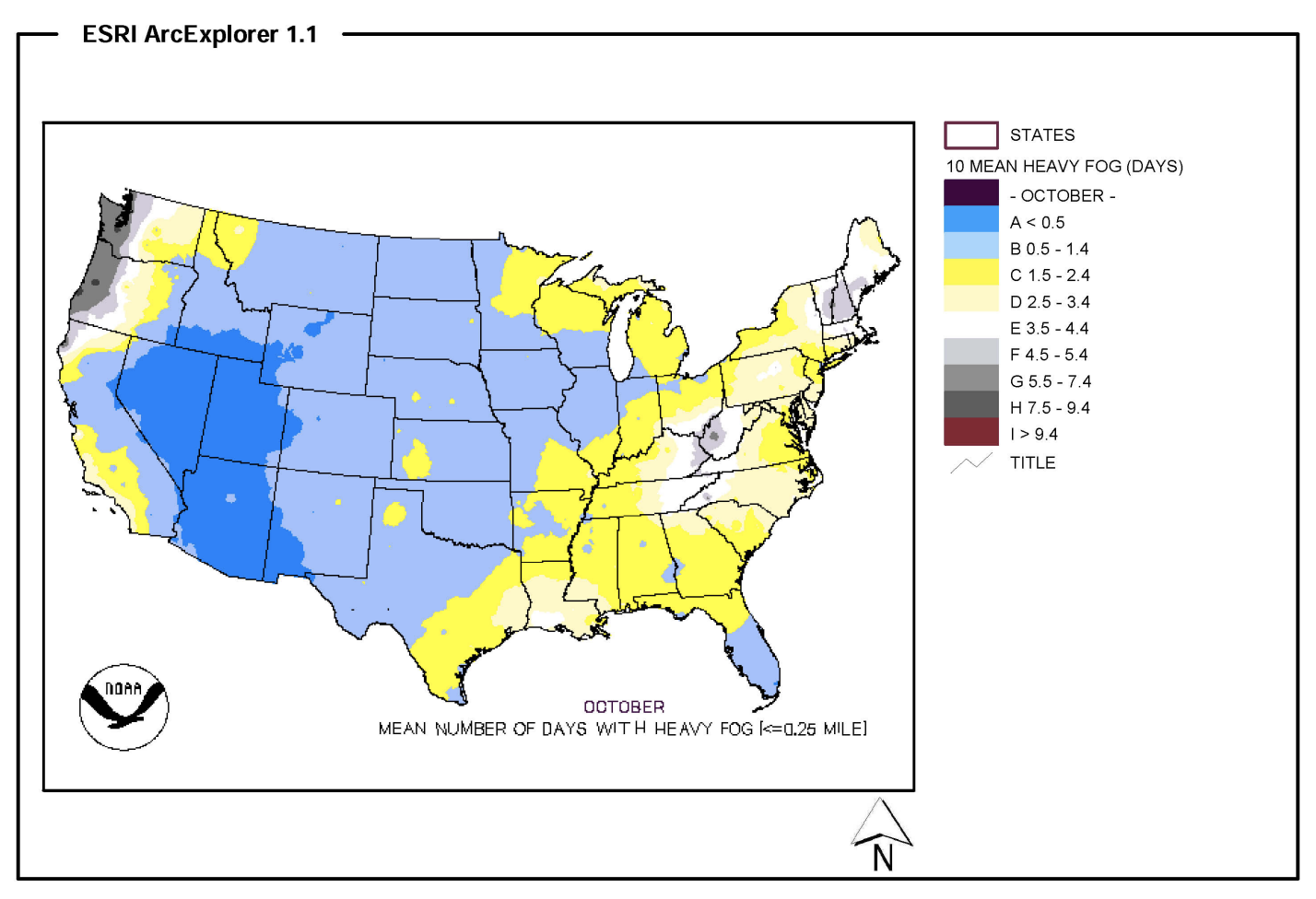

Days that include heavy fog, i.e., visibility less than or equal to 0.25 mile, occur during October more often west of the Cascade Mountains than any other region of the lower 48 states (Figure 1). It is usually of the “radiation fog” variety. It is caused by the cooling of the ground, and the adjacent air, to the dewpoint (saturation) temperature due to a net upward flux of infrared radiation (IR). The cool air near the surface is generally capped by much warmer air of lower density, which serves to inhibit mixing. Completely calm conditions are not usually as favorable for the development of radiation fog as light winds. The latter are accompanied by a modest intensity of turbulence which tends to deepen the cool layer near the surface, which otherwise can be quite shallow. A deeper layer means that much more fog, and once it forms, the fog tends to perpetuate itself. The fog serves to reflect most of the incoming solar radiation, which delays and reduces the daytime heating, thereby keeping the near-surface air cool enough to remain saturated.

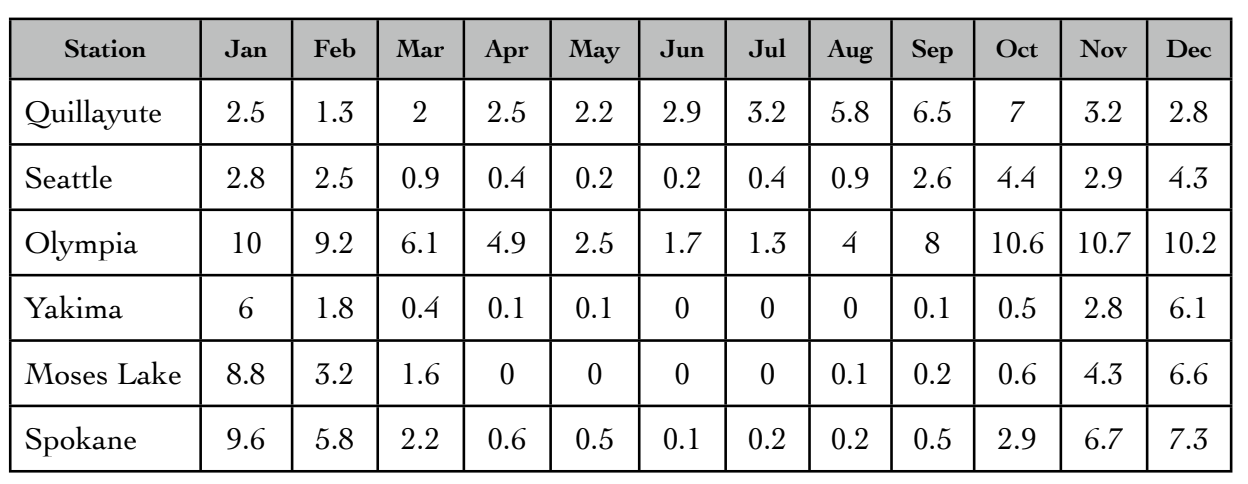

How does the incidence of fog in early fall compare with that during other times of year? Table 1 itemizes the number of days per month with heavy fog at three western WA stations (Quillayute, Olympia, and Sea-Tac) and three eastern WA stations (Yakima, Moses Lake and Spokane) based on local climatological data (LCD) for 1996-2008 compiled by the Western Regional Climate Center. The table shows that heavy fog is relatively common in western WA in early fall, but also occurs routinely at other times of the year. For eastern WA, heavy fog is most prevalent in winter (more about this will be included in a future newsletter). Fog is favored in western WA during the early fall because the Pacific storm track is generally situated north of the state into the Gulf of Alaska. When this is the case the air aloft over our region is often relatively dry, and the nights are long enough for considerable radiational cooling. At the same time there can be reasonably moist air near the surface due to evaporation from the ground that has already been wetted to an extent by recent rains and regional waters that are still relatively warm. Moreover, the winds in these synoptic situations are generally light, and so all the ingredients are in place for radiation fog. It is especially common in Olympia since that location tends to cool down at night much more than other western WA locations (Arlington north of Everett is another ice box).

As mentioned above, it is no cinch to accurately forecast fog. It is especially difficult to anticipate how long it will persist and whether it will transition to more of a stratus deck or dissipate in place. One good if not absolutely sure bet is that when it is foggy in the lowlands that it will be sunny and warm in the mountains. Some of the best hiking and climbing in early fall is when it is socked in at low elevations. And one can often estimate how high to go to get out of the gloom through inspection of high-resolution visible satellite images.