Skill in ENSO Model Prediction

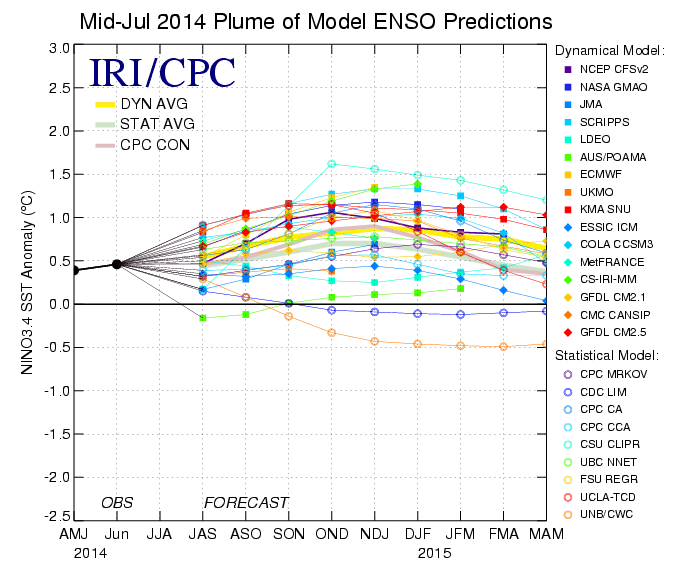

We have previously discussed the skill of seasonal weather predictions for winter in this newsletter (March 2014 edition). One of the most important sources of information for these seasonal forecasts is the future state of El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO). An ENSO warm event (El Niño) seems likely for the upcoming winter, as indicated in the set of predictions from modeling centers around the world shown in Figure 1. This El Niño is taking its sweet time in development, and so how much should we trust these kinds of predictions?

Considerable effort has gone into assessing the skill of present-generation ENSO models. A recent review of the topic is provided by Barnston et al. (2012); some excerpts from that paper are reproduced below. Once formed, the maintenance of an El Niño or La Niña event is reasonably well understood. Air-sea interactions in the tropical Pacific are crucial, with mutual reinforcement between the atmospheric and oceanic anomalies. On the other hand, we have much less understanding of the mechanism(s) that kick ENSO from one state into another. This is reflected in the diversity in the statistical models for ENSO prediction, which key on different variables in the atmosphere-ocean system. The dynamical models are more alike in principle, but nevertheless generally yield a range of forecast trajectories, as in the example shown in Figure 1.

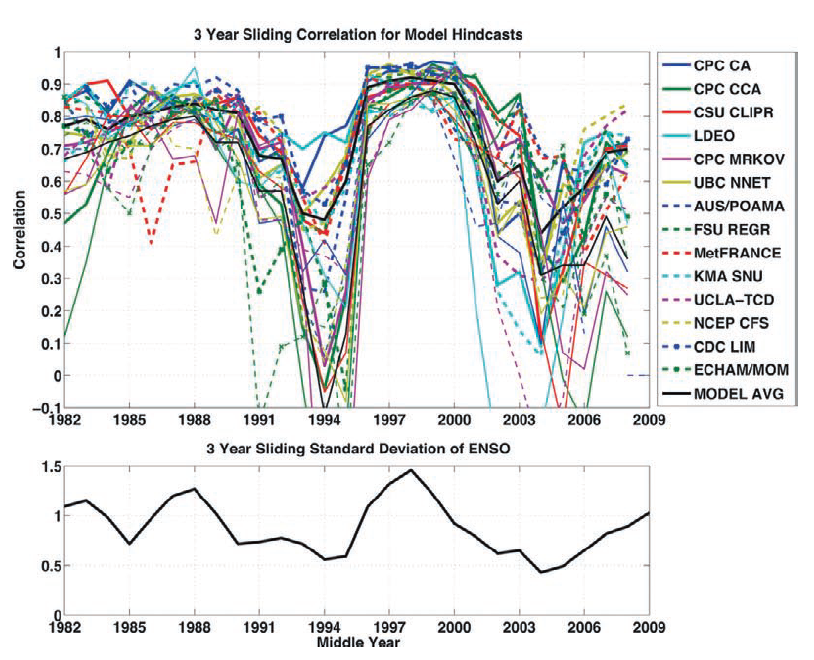

The predictability of ENSO also varies on multi-year time scales. As shown in Figure 3 (also lifted from Barnston et al. 2012), 2002-2011 was a period of relatively low predictability, with smaller correlations between model ENSO predictions and observations than during much of the period of model validation. This relates to the weak amplitude of ENSO during that same period (lower panel of Figure 3). Since predictability was low in 2002-2011, perhaps the results shown in Figure 2 reflect the lower limits on model skill.

The consensus of the models is that there will be an ENSO during the upcoming winter that will be strong enough to impact the global-scale atmospheric circulation. Of course, we do not know how it will play out exactly in terms of the weather of our region, but we’ll be watching.

periods is shown in the bottom panel. [From Barnston et al. 2012]

References

Barnston, A.G., M.K. Tippett, M.L. L’Heureux, S. Li, and D. G. DeWitt, 2012: Skill of real-time seasonal ENSO model predictions during 2002-11 – Is our capability increasing? Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 93, 631-651.