Growing Hops in Washington State

Due to the passage of I-502 by Washington state voters in November 2012, legal agricultural production has commenced for a notorious member of the family Cannabacaeae. This highlight is about another member of this family that WA state is known for and that is hops (Humulus lupulus). The female flowers, also known as cones, from hops constitute an essential flavoring ingredient for most beers. Hops have been grown in the Pacific Northwest since the late 1800s, and presently about 75% of the commercial production of hops in the United States occurs in the Yakima Valley. What makes this place so special for this particular crop, and should we worry about how its suitability may be impacted by expected changes in the climate?

Hop vines are rather demanding. They are vigorous climbers with as much as a couple feet of growth per week. This kind of growth requires abundant sunshine, nutrients and lots of water, typically 20-30” per season. But consistently low humidity is also needed to suppress the development of fungal diseases such as downy mildew that are favored in warm, wet conditions. The Yakima area certainly fits that bill with average relative humidity values of about 25-30% in the afternoon and only about 70% during the late night and early morning hours. The prevailing winds are from the west-northwest, which means downslope flow off the Cascade Mountains. While the Cascades produce a rain shadow in the Yakima Valley, they also serve as a sort of water tower, with mountain reservoirs in the form of winter snowpack generally providing sufficient water for a variety of agricultural and recreational interests, including the growers of hops.

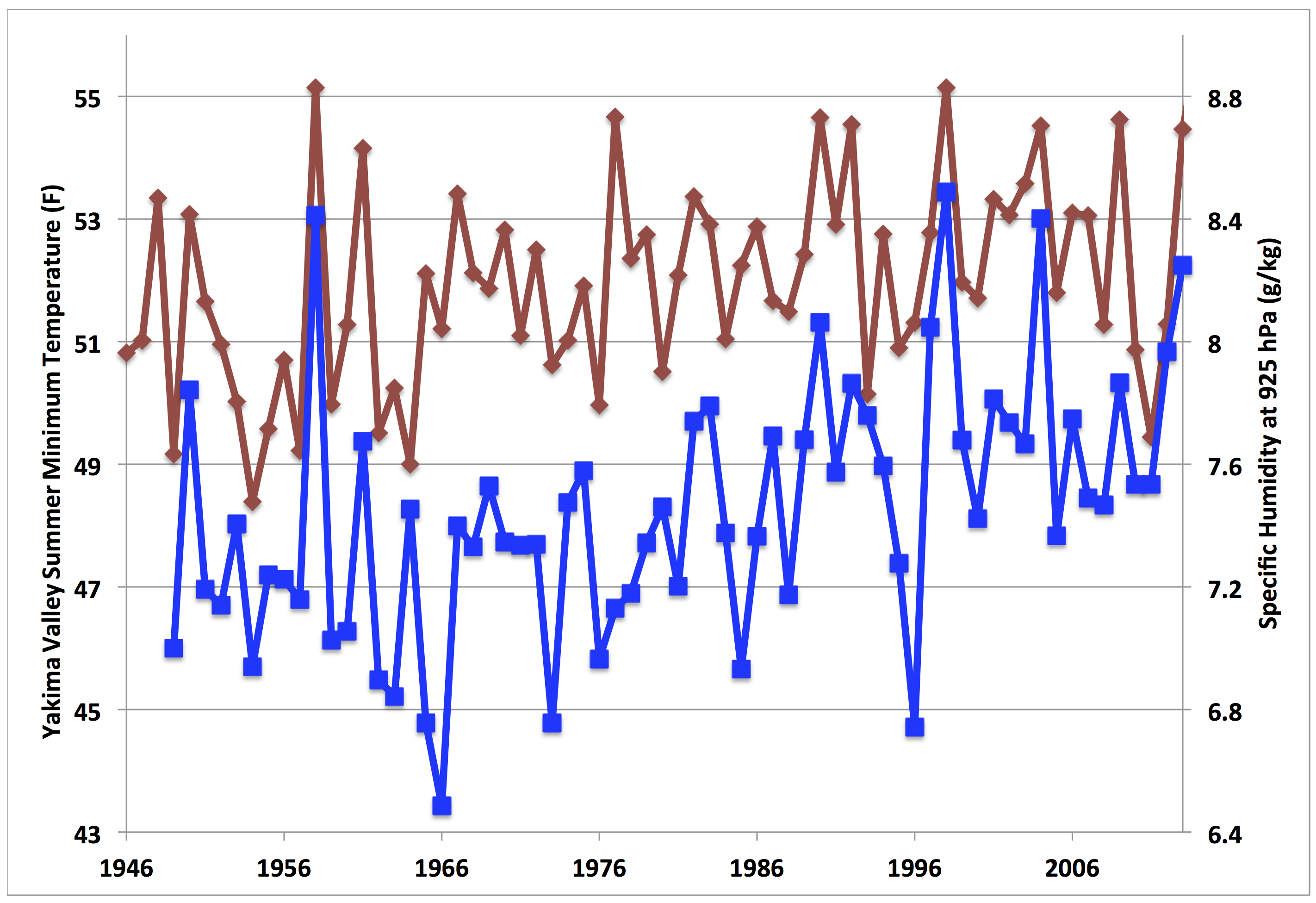

On the subject of climate change and its potential impacts on the farming of hops in the Yakima Valley, we will take two approaches. First, we examine the historical record of summer conditions in the region. Here the focus is on the trends, or lack thereof, in two related parameters, average minimum temperatures from three stations in the Yakima Valley (Yakima Airport, Moxee, and Sunnyside) and low-level absolute humidity from the 925 mb level of the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis over a similar region. Time series of these parameters are shown in Figure 1. The record of the June-August average minimum temperatures as a whole includes a slight upward trend but primarily features considerable year-to-year variability. Most of the summers with especially high minimum temperatures are coincident with positive anomalies in absolute humidity. There is a more prominent upward trend in this parameter, at least over the last two-thirds of the 60+ year record considered here. It is unknown whether this rise in humidity has been accompanied by more frequent incidences of fungal diseases and other pathogens on hops, but it is still typically quite dry in a relative sense. It would therefore seem unlikely that even a continued increase in humidity would have substantial near-term (on climate time scales) effects on Yakima Valley hops. The longer-term changes in the summer weather of the region could be a different story, upon which we speculate in the second part of this summary.

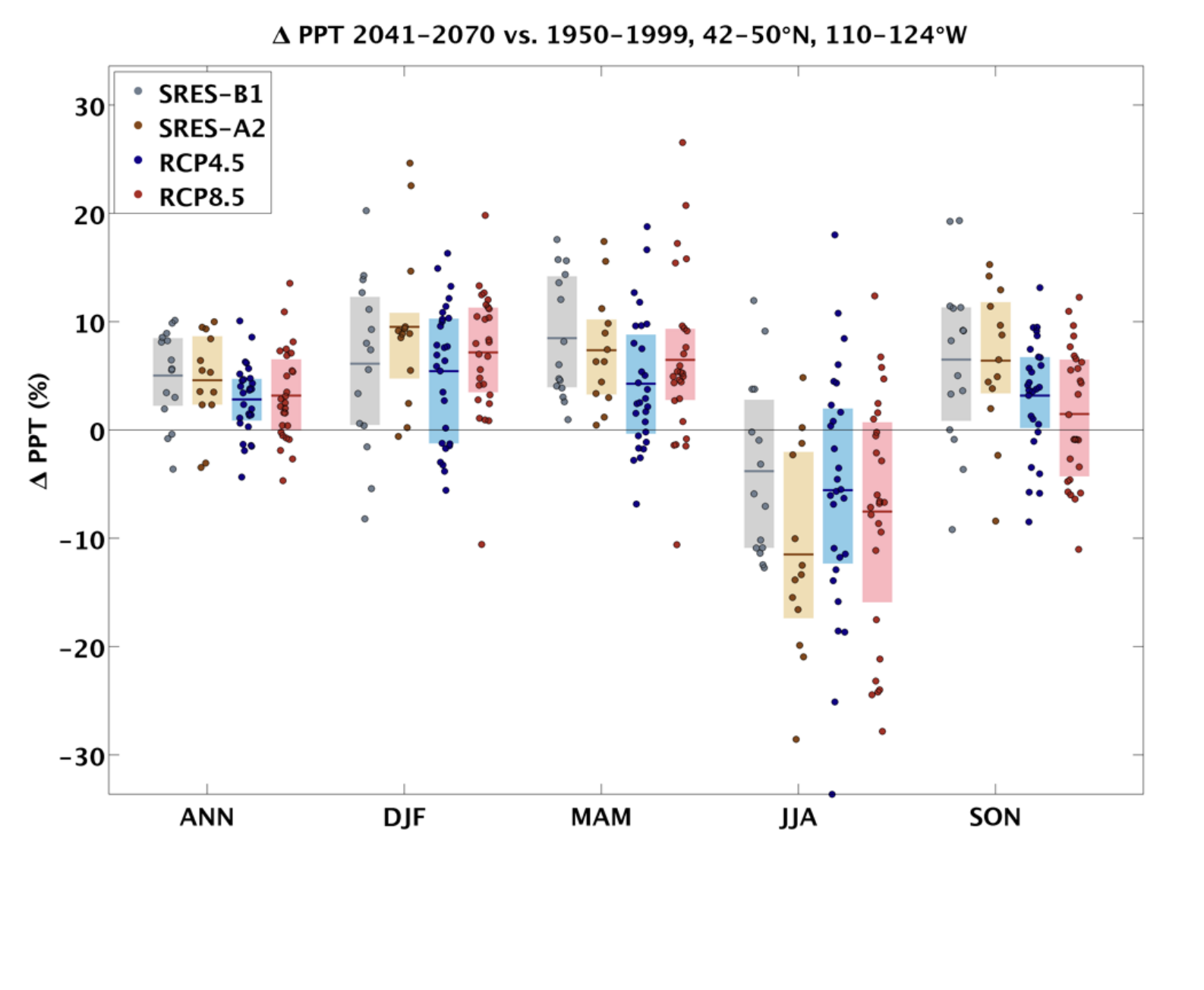

The future climate may lead to both a greater need, and a reduced supply, of water for the Yakima Valley in summer. Climate model projections of precipitation in the Pacific Northwest are suggesting wetter winters and drier summers, with plenty of uncertainty, as illustrated in the ensemble of model results for the middle of the 21st century in Figure 2 (from Dalton et al. 2013). There is greater confidence that there will be warming, which is expected to lead to reduced snowpack, and hence less water in that part of the Northwest’s “water bank”. The bottom line is that trade-offs may be necessary among the various competing interests that rely on the water available for the Yakima Valley. Presumably hops will continue to get their share, at least if beer aficionados have anything to do with it.

References

Dalton, M.M., P.W. Mote, and A.K. Snover [Eds.]. 2013. Climate Change in the Northwest: Implications for Our Landscapes, Waters, and Communities. Washington, DC: Island Press.