Springtime Floods in Eastern WA

Winter is winding down in the Pacific Northwest, which means that floods are becoming less and less likely on many of our streams. In particular, rivers draining watersheds at mostly lower elevations, especially on the west side of the state, tend to experience their greatest streamflows from fall into the middle of winter in association with heavy rains. But what about those watersheds that are dominated by late fall and winter precipitation in the form of snow? The rivers draining those watersheds typically have their peak flows of the year in spring due to snow melt, often in combination with rain. Are they generally just a nuisance, or can they represent significant, damaging floods? We decided to take a look.

Our procedure involved examining the Storm Events Database maintained by NOAA that is available at the following website: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/stormevents/. Focusing on just the counties east of the Cascade Mountains crest, we counted up the number of “Flood” and “Flash Flood” events that are in this database during the period of 1 December 2004 through 30 November 2016. We could have considered a period going back a bit farther in the past, but relatively few events are listed in this database prior to the early 2000s.

We assume that the 12 years analyzed here is sufficient to provide an indication of frequency and severity of floods in eastern WA at least in relative terms. Our method was simple, and that was to determine the total number of flood and flash flood days by county during the months of March through May, and compare them with totals for the entire year.

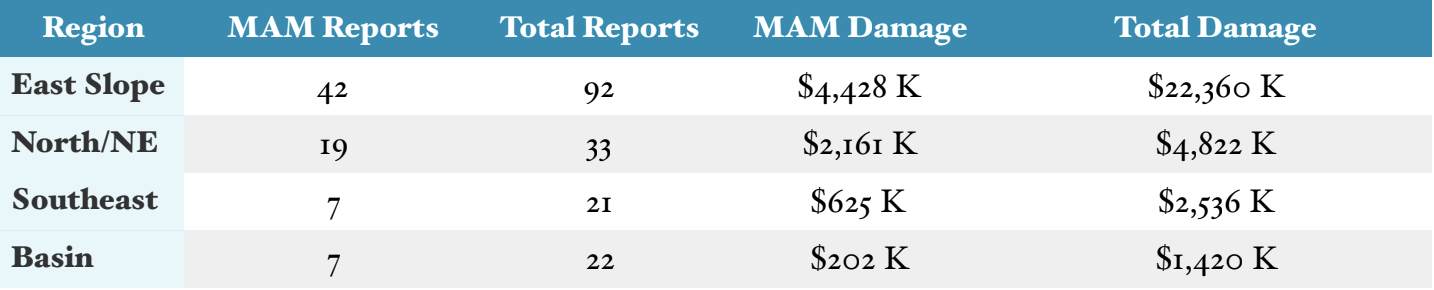

We also added up the dollar damages listed during the three months of March through May, and for the 12 years as a whole. For convenience’s sake and because we’re more interested in the seasonality of the floods, we did not worry about flood events being counted multiple times, i.e., because of their impacts on more than one county. In other words, the results shown below reflect the numbers of reports, and not the numbers of events. We have also grouped the results for the eastern WA counties into four geographic regions: East Slope of the Cascades (Okanogan, Chelan, Kittitas, Yakima and Klickitat), North/Northeast (Ferry, Stevens, Pend Oreille, and Spokane), Southeast (Whitman, Garfield, Asotin, Columbia, and Walla Walla) and Columbia Basin (Douglas, Grant, Franklin, Benton, Adams, and Lincoln).

The results from our quick analysis are itemized in Table 1. First of all, floods, at least as reported in the Storm Events database, are much more common in the East Slope than in the other regions. They are least common in the Southeast and Columbia Basin regions. With respect to the seasonality, floods occur in spring (March through May) relatively often in the East Slope and especially the North/Northeast regions. For the latter region, the cost of the damages of the spring floods is also disproportionately high, specifically about one-half the total in one-quarter of the time. Its greatest monetary loss in the period examined here (about 1.6 million dollars) was the flood in Spokane County on 19 May 2008 caused by unseasonably warm weather and rapid snowmelt. On the other hand, for the East Slope counties, the most damaging floods tend not to occur in spring, but rather in winter. This region did have a costly flood on 15 May 2011 in Kittitas County (~4 million dollars) in association with a combination of snowmelt and heavy rain accompanying thunderstorms. Springtime floods do not appear to be much favored in the Southeast and Columbia Basin regions. The streams of the lower elevation Columbia Basin counties would not seem to be sensitive to rapid snowmelt and hence the lack of major springtime floods is no surprise. The counties of the Southeast region do have some rivers with watersheds extending up to higher terrain, but major floods have not occurred that often in spring during the last 12 years.

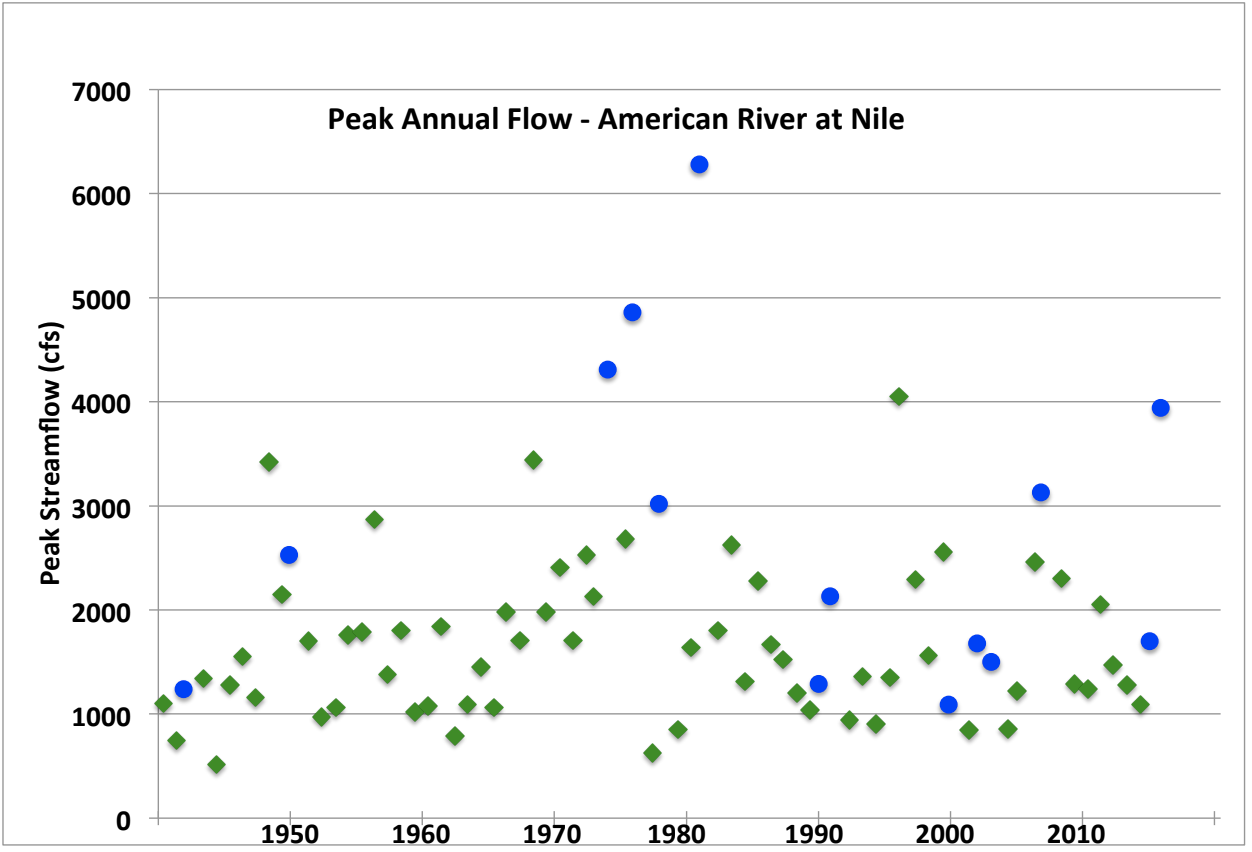

We were also curious whether there are any noticeable trends in the magnitudes of springtime streamflows in eastern WA. Addressing this issue properly is way outside the scope of the present piece. We did take a look at one stream, the American River of Yakima County. It is unregulated, and may be representative of streams on the east slope of the Cascades. A time series of its peak annual streamflow each year back to 1940 is shown in Figure 1. Note that most of the values are shown in green, signifying peak flows occurring in the spring (usually May). The blue dots show instances when the peak flows have occurred earlier in the water year (November through February) presumably due to heavy rain. There are more peak flows during the winter in the latter portion of this record, but other than that, there does not seem to be any systematic change in the typical magnitude of the peak flow.

The lack of a decline probably signifies that snowpack in its watershed is not going downhill fast (pun intended), with the notable recent exception of 2015. This is a good thing, since the Yakima Valley relies on late spring snowmelt for much of its water supply during the growing season.