Timing of Major Floods on 6 Rivers in WA State

The dry weather of autumn 2019 in an overall sense resulted in relatively low streamflows throughout most of WA state, but that story has changed drastically since late December. Since then there have been several periods of above normal streamflows with a number of rivers spilling over their banks. Now that we’re seeing some floods, especially west of the Cascade Mountain crest, we were wondering: do major floods always occur when streamflow is climatologically high?

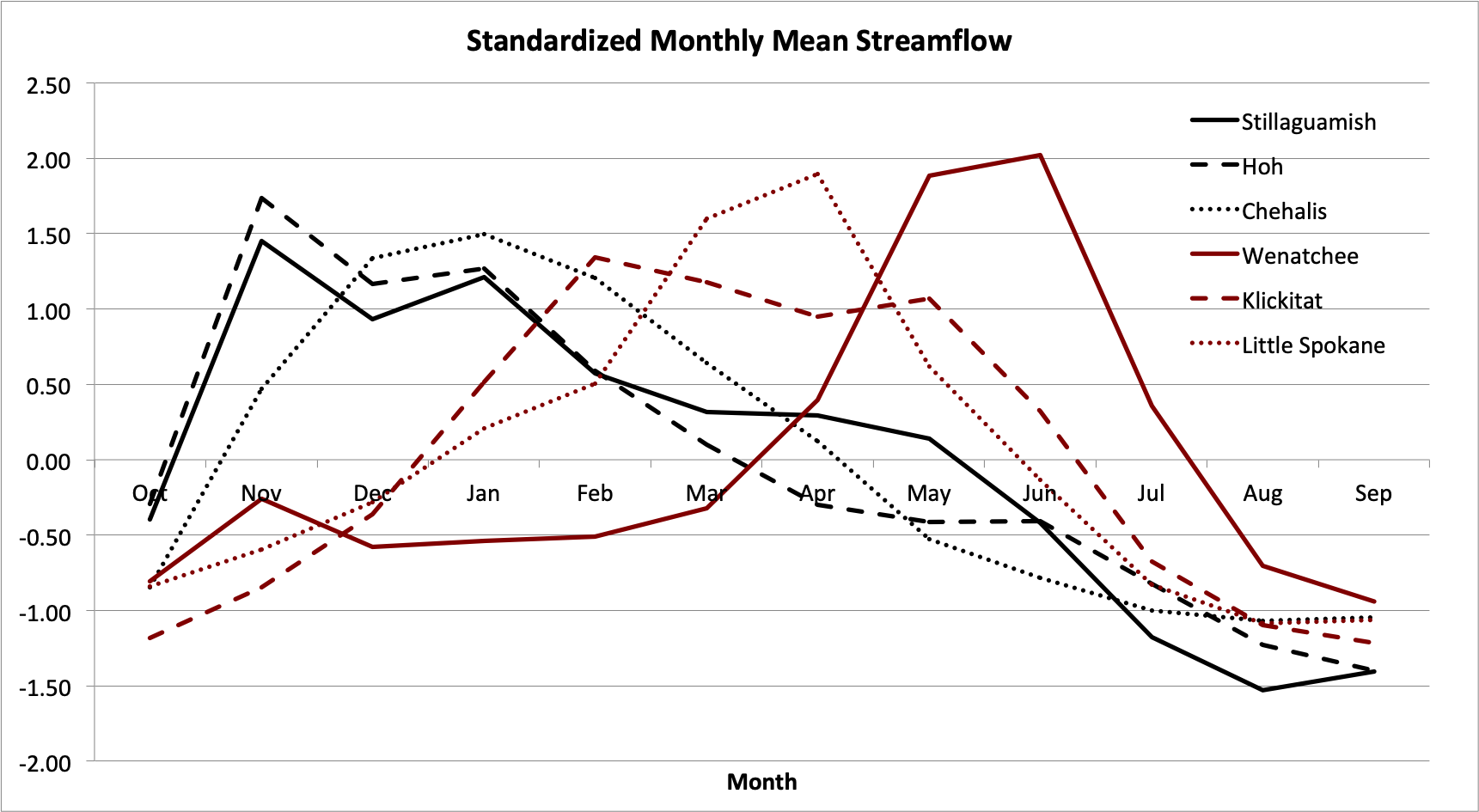

Towards that end, we considered 6 mostly unregulated rivers – 3 in western WA and 3 in eastern WA – and examined the standardized monthly mean streamflow and the timing of the top 20 peak streamflow events. The records are all relatively long and are as follows: Chehalis River at Porter (1947-2017), Hoh River at Highway 101 (1961-2017), Stillaguamish River at Arlington (1929-2017), Little Spokane River at Dartford (1929-2019),Wenatchee River at Peshastin (1929-2019), Klickitat River at Pitt (1929-2017).

Figure 1 shows the monthly mean streamflow in standardized format for all 6 rivers, illustrating some major distinctions that can be made for these rivers. The Chehalis River is the most rain dominant of the bunch, and is classified as such. Rain dominant basins have their highest streamflow in the fall, when most of the basin precipitation falls as rain. The other western WA rivers –the Stillaguamish and Hoh – have their highest flows in the fall as a response to rain as well, but they also have an increase in monthly streamflow in April/May (Stillaguamish) and June (Hoh). These are known as “mixed basins” since there is a clear contribution to streamflow from melting snow at higher elevations. The Klickitat is also a mixed basin, with peaks in both February and May. Finally, the Wenatchee River is an example of a “snow dominant” basin; May and June have relatively high streamflows due to the snowmelt contribution. The Little Spokane is a snowmelt basin as well, with an earlier peak streamflow in April. It is worth pointing out that all of the rivers, regardless of their classification, have their lowest flows in August and September, a time of year when much of the state has its greatest need for water. Perhaps the monthly timing of the peaks and nadirs of streamflow are already well- appreciated, but do they necessarily line up with the major floods occurring on these rivers?

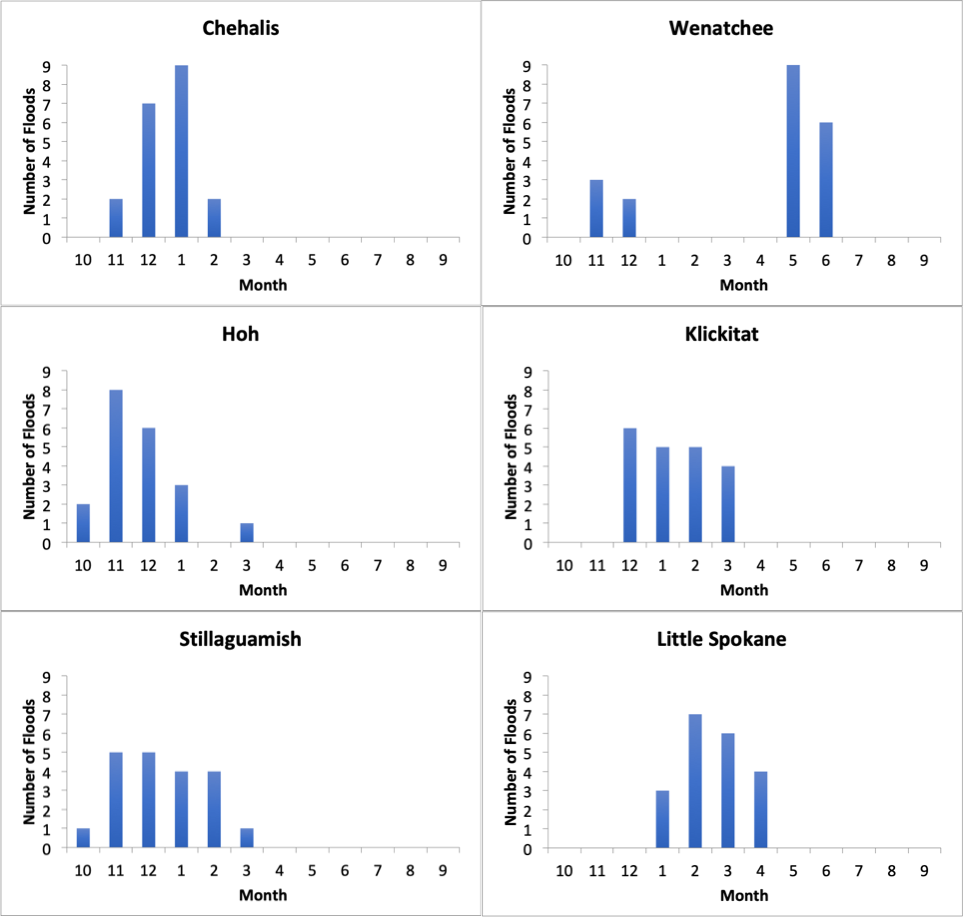

Figure 2 shows the timing of the top 20 peak flow events for each river, and the results are not entirely intuitive. The Little Spokane, for example, has its major floods relatively early in the calendar year (Jan-Apr) despite it being a snowmelt dominated river. The Wenatchee, on the other hand, clearly gets its biggest floods during the May and June snowmelt season. Nevertheless, that doesn’t mean it never experiences floods during fall. Five of the top 20 peak flows on the Wenatchee occurred in November or December, so it’s still a risk in a snow-dominant basin. Some less surprising results came in for the Chehalis; this rain dominant river has had the lion’s share of its floods in December and January.

One wrinkle here is that the mean streamflow in February remains relatively high during a time of year when the frequency of major flood events drops off. That being said, the flood of early February 1996 on the Chehalis was a real doozy (the second greatest in its entire record). The Hoh River, on the SW Olympics downstream of some of the highest annual precipitation totals in the state, sees early fall flooding and none of the top 20 peak streamflows occurred during the snowmelt season. Similar results are shown for the Stillaguamish, but it’s interesting that its top 20 peak streamflows are more evenly distributed through the fall months than those on the Hoh or Chehalis. Finally, on the Klickitat, there aren’t peak streamflows from snowmelt in the spring here despite it being a mixed basin with two peaks in mean monthly streamflow. The greater flows seem to be more rain dominated than might be expected.

To summarize, there are some surprises regarding the timing of the peak streamflows compared to the when the mean streamflow is highest, but most of the historical floods on these 6 rivers occur in the month in which the mean flows are already high (ex. Hoh, Chehalis, and Wenatchee). Still, the historical record indicates that major flooding could occur on many of our rivers anytime from October through June, despite the basin type. Those impacted by river flooding are well-advised to stay informed of the latest forecasts from the National Weather Service through the entirety of the wetter part of the year.