A Tale of Two Sea Surface Temperatures

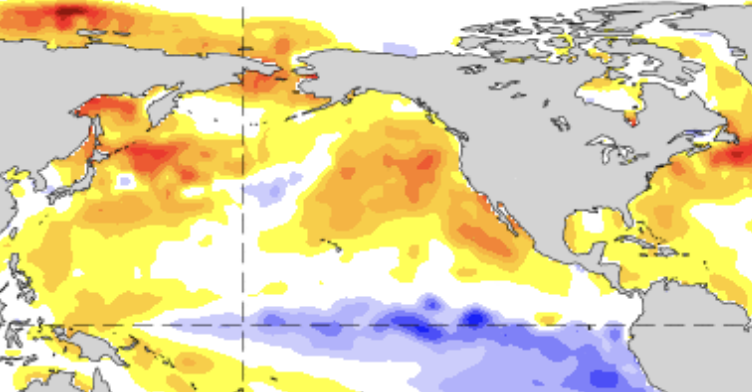

There is a strong indication that at least moderate, and possibly strong, La Niña conditions will be present during the upcoming winter of 2020-21. Many readers of this newsletter know of the implications for WA state, namely improved odds of seasonal mean weather on the wet and cool side and healthy snow totals in the mountains at the end of winter. The sea surface temperature (SST) in the eastern and central equatorial Pacific is already considerably colder than normal, as shown in Figure 1. But wait a minute. Note that the upper ocean is warmer than normal off the coast of the Pacific Northwest and conceivably that loads the dice for a toasty winter. We explore that a bit here.

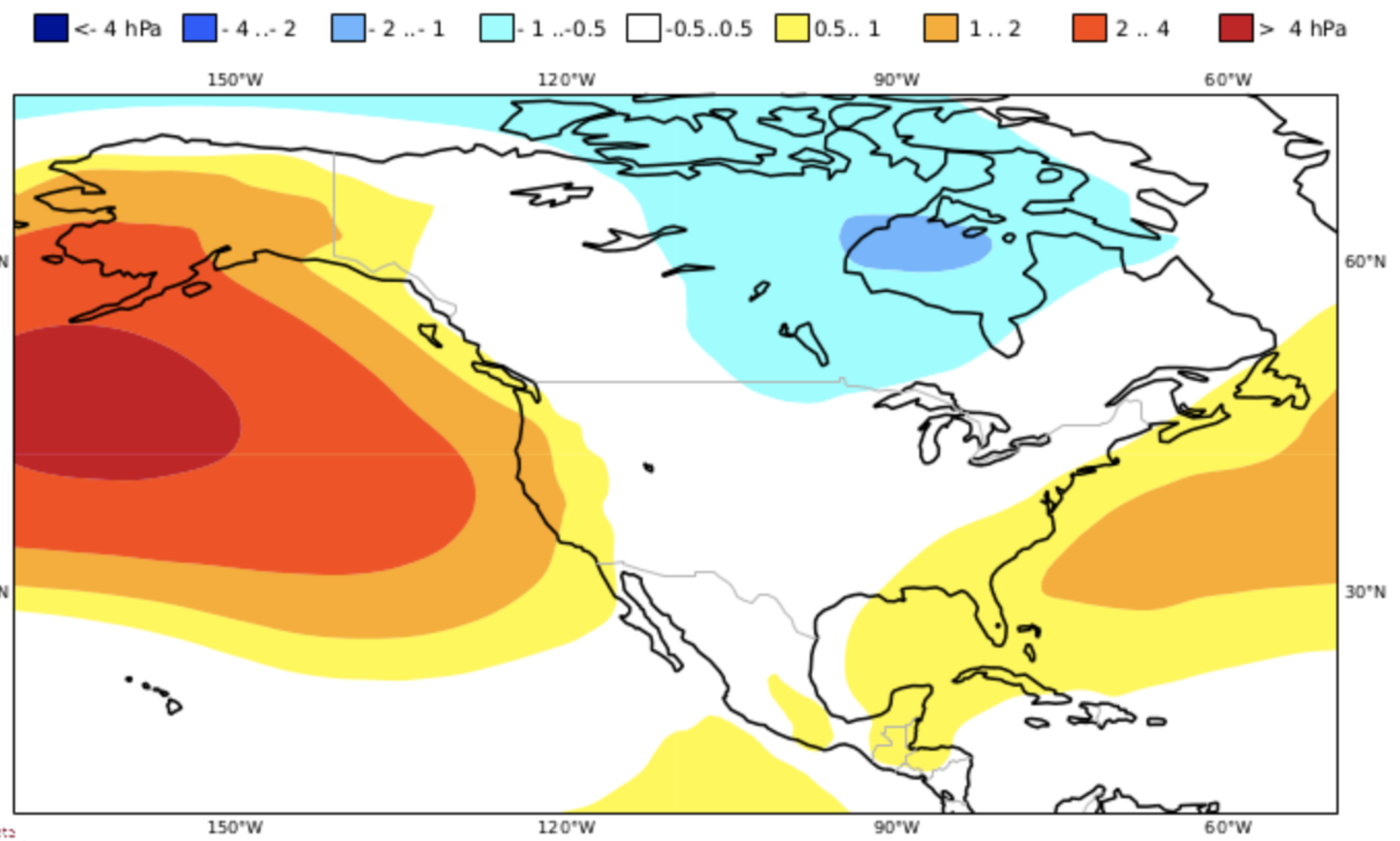

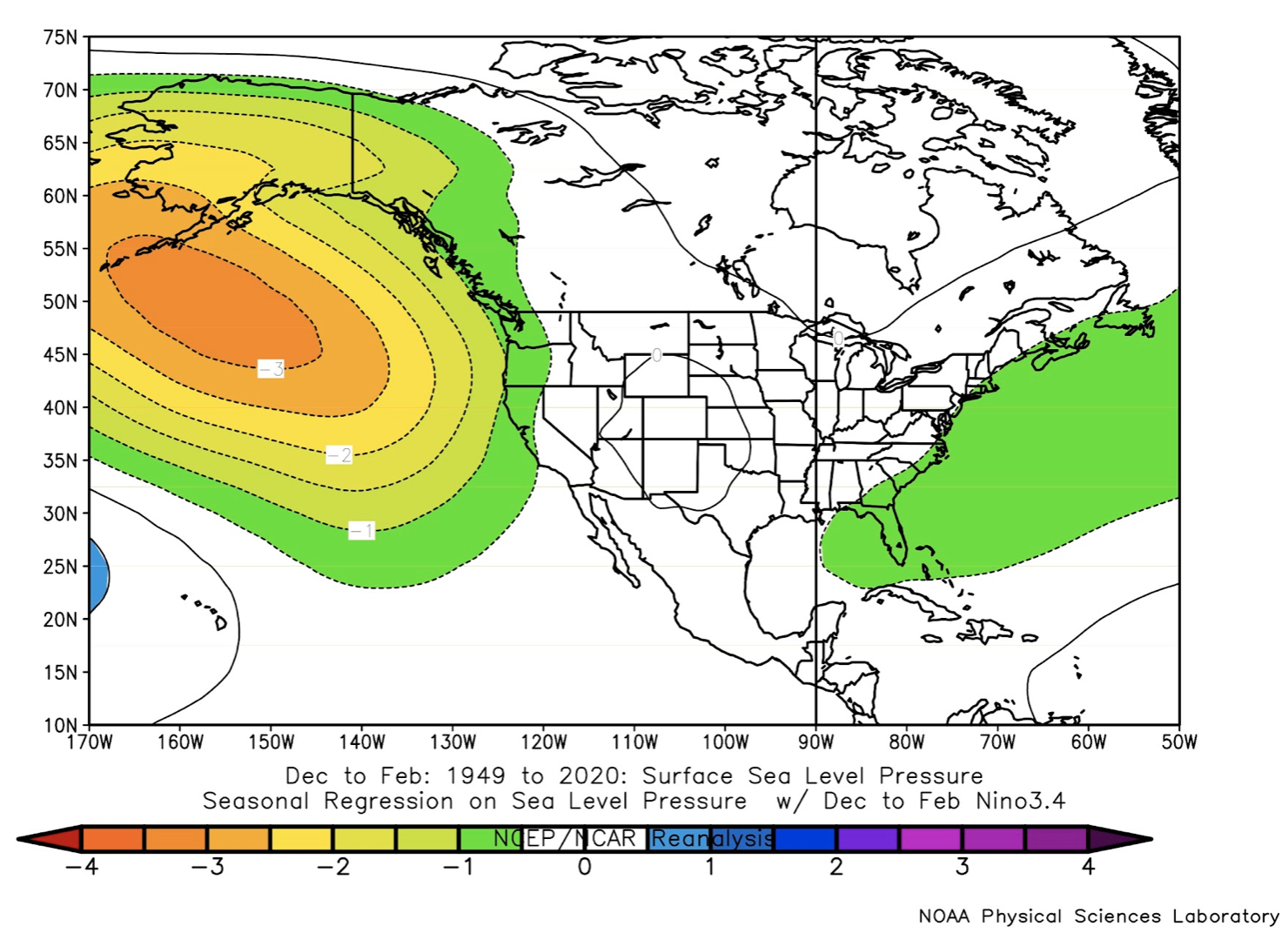

To begin, we consider the prospects for our winter associated with La Niña. The coupled ocean-atmosphere climate models used for seasonal weather prediction can account for the state of the tropical Pacific and as a group, reflect a robust atmospheric response over the North Pacific Ocean and North America that is typical of La Niña. An international multi-model ensemble mean prediction of the sea level pressure (SLP) anomaly distribution during December through February, based on October model runs, is shown in Figure 2. Of significance to our winter weather is the higher than normal SLP forecast south of western Alaska, i.e., an abnormally weak Aleutian low. The circulation associated with this kind of SLP anomaly distribution features NW low-level flow for the Pacific NW and a tendency for more weather disturbances out of the Gulf of Alaska, often accompanied by cool and wet weather. It is also bad news for California and the desert Southwest, which experience substantially suppressed storminess and precipitation in this kind of situation. The idea that the climate models are effectively “buying in” to La Niña is indicated by comparing the composite SLP anomaly forecast of Figure 2 with the past atmospheric response to La Niña, as shown in the regression between the observed winter SLP and the NINO3.4 index included here as Figure 3. There is a close similarity between the pattern of the SLP signal over the North Pacific in Figures 2 and 3. Considering that ENSO models are forecasting a NINO3.4 value of -1 to -1.5 for the winter ahead, the regression on past data yields an expectation of a positive SLP anomaly of about 4 mb, which is close to the value predicted by the models. Further support for this La Niña playing a major role in our weather is provided by previous work by CICOES researcher Andrew Chiodi, who found that La Niña events that included a prominent suppression of deep cumulus convection in the western tropical Pacific were accompanied by an atmospheric response in the North Pacific that was 3-4 times stronger than those winters that were labeled as La Niña based on the overall SST anomaly distribution in the tropical Pacific, but for whatever reason(s) lacked much of an expression in terms of central and western Pacific convection. Based on the observed convection with the present La Niña, it is on track to qualify as the type of event that is accompanied by enhanced precipitation in WA (A. Chiodi, personal communication).

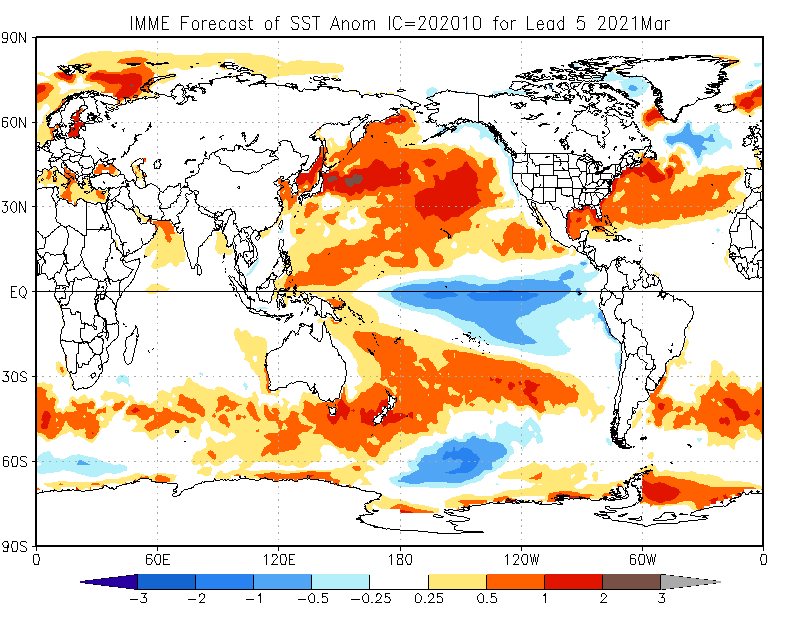

OK, fine, La Niña is liable – but of course not guaranteed – to bring joy to winter sports enthusiasts and other interests depending on mountain snowpack, but what about that warm water off our coast? Is there the potential for the disaster of 2014-15, which is famous for both the extremely warm water off the coast and the record high winter temperatures and low snowpack? The short answer is almost certainly no. To begin with, while the SSTs off our coast are elevated, the depth of the warm water appears to be considerably less than at the same time of year in 2014 (not shown). More specifically, the temperature at the 50 meter deep level were more than 1°C higher in the September of 2014 than 2020. In other words, there is not nearly as large a reservoir of extra heat in the upper ocean, which means it can cool off relatively rapidly depending on the atmospheric forcing. And the atmosphere may well cooperate, given La Niña. As illustrated by the model projections and historical averages associated with La Niña, it is expected that wind anomalies out of the northwest will prevail for the winter season as a whole. This sense of flow results in coastal upwelling, bringing up cooler water from depth that can rapidly decrease surface temperatures. That process is important for a narrow strip near the coast, but northwest flow also tends to cool off the upper ocean farther offshore. In that region of deeper waters, northwesterly flow is accompanied by relatively cool air masses leading to enhanced fluxes of heat from the upper ocean to the atmosphere. It also forces equatorward upper ocean currents (Ekman transports) and hence the advection of colder water from the north. These effects do not occur day in and day out, but if in fact, there are northwesterly wind anomalies for the winter as a whole, the present warm SSTs along the coast probably will not plague us, nor the juvenile salmon that enter the marine environment next spring. This scenario is consistent with the climate model projections for March 2021 (Fig. 4), which indicate SSTs along the coast that are actually on the cool side. As an aside, the models have the upper ocean remaining warm well off the coast; the high SLP that is forecast in the central North Pacific means less storminess, and the weaker winds mean reduced surface heat fluxes out of the ocean and less stirring up of cooler water from below.

The bottom line is that if the winter plays out as expected, we should have at least a decent snowpack going into spring. This happens to be a La Niña for which the models are forecasting a more robust signal for precipitation rather than temperature, and so the prospects for especially cold temperatures are not all that high. On the other hand, we also need to take what we can get since most of our winters in recent years (with 2016-17 being an exception) have been on the warm side.