Timing of Seasonal Changes in the Weather of Washington State

This corner of our newsletter has recently concerned the seasonality of weather events in Washington state, and we continue in a similar vein in the present edition. More specifically, we consider average changes in temperature and mean precipitation on a daily time scale over the course of the year for selected locations in Washington. The autumnal equinox is in the rear-view mirror, of course, and so it is officially fall based on the astronomical definition. On the other hand, the “meteorological” fall is often considered to begin on 1 September, with the other meteorological seasons also 3 weeks ahead of their astronomical counterparts. What definition actually makes the most sense given the observed weather in the state? Moreover, are our seasons symmetrical, i.e., each 3 months in duration from a weather – not day length –perspective? Here’s your chance to find out.

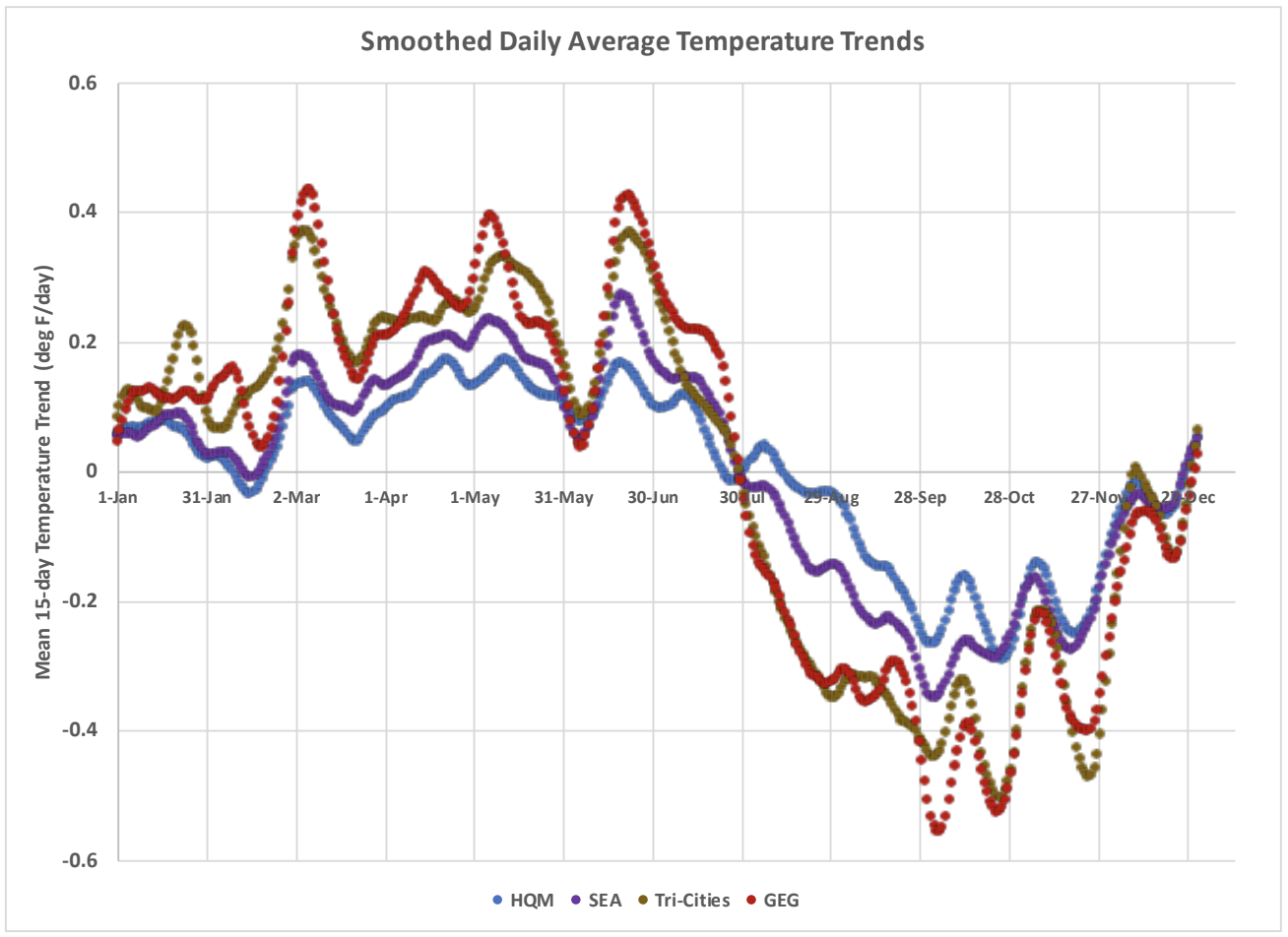

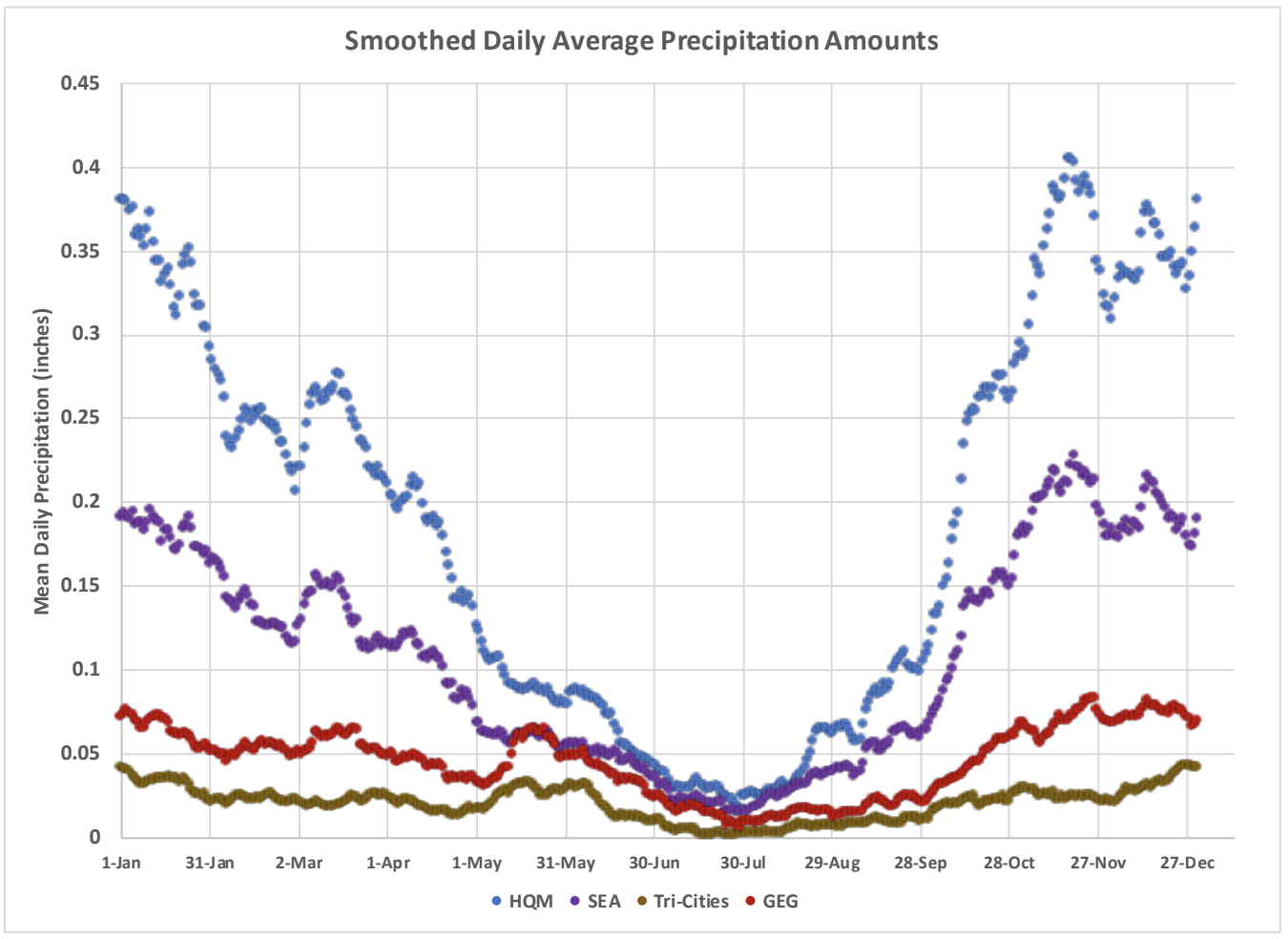

The present analysis is based on daily mean temperature and precipitation amounts for the years of 1991 through 2020 at four locations: Hoquiam (HQM), Sea-Tac (SEA), Tri-Cities, and Spokane (GEG). The mean temperatures and precipitation totals for each calendar date were subject to 15-day running-mean averaging to reduce the day-to-day variability associated with high-amplitude events that are reflected as noise in the 30-year means. Greater and lesser smoothing was explored with the single 15-day averaging appearing to strike a reasonable balance between filtering out much of the more or less random fluctuations while retaining meaningful seasonal trends on shorter time scales. For the temperature records, we also computed 15-day best-fit linear trends for each calendar date to better highlight the changes in average temperature over the course of the year. The results for temperature and precipitation are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

The temperature trends on a 15-day time scale over the course of the year (Figure 1) are worth staring at for a while. Note that the rates of warming early in the year and of cooling late in the year are much greater east of the Cascades in the Tri-Cities and Spokane, as expected given their more continental influences. What is a bit of a surprise is the coincidence in the transition from warming to cooling at the very end of July at three out of the four stations, with Hoquiam lagging by about 2 weeks (based on an eyeball smoothing of its trace). This lag makes sense given the thermal inertia of the ocean, which continues to warm later into the year. It also is interesting that all four stations stop cooling essentially at the end of the calendar year. In other words, there is warming in January, albeit not at the rate that occurs in a couple of months. The period of greatest warming, which could be the basis for defining “spring”, occurs from the beginning of March through June and hence is arguably 4 months in duration. By way of comparison, the pronounced cooling of fall is compressed into something more like 2 to 3 months. Figure 1 indicates there is usually marked cooling in early October in stark contrast with the present year, which features a summer that refuses to end.

Normally, we would also be experiencing periods of significant rain, as illustrated by the precipitation time series of Figure 2. Daily average amounts really ramp up over the course of October; we are liable to get into a more typical weather pattern before too long, so consider yourself forewarned. At least for Sea-Tac and Spokane, it can be argued that the increase in precipitation (“fall”) occurs typically over an interval of 2 months (October and November). The period of decrease in precipitation west of the Cascades (at least at HQM and SEA) is from near the start of the calendar year into July, and by this measure “spring” is about 6 months long! The decreases in precipitation during the first half of the year are not nearly as marked in the Tri-Cities or Spokane. Those two locations happen to have local maxima in their mean daily precipitation from early May into June. Spokane has actually received slightly more precipitation than Sea-Tac during some days in late May for the 30-year period considered here.

To address our question of meteorological vs. astronomical fall posed in the introduction, we can have it both ways in Washington state. According to these 4 stations, it appears as if September 1 is a better fall definition for western WA while astronomical fall is a better definition for eastern WA. HQM and SEA have more distinct temperature drops and precipitation increases in September compared to their counterparts in eastern WA, where the change happens closer to the end of September and early October.

It is outside the scope of the present piece, but it would be interesting to determine the extent to which the seasonality of the temperature and precipitation in WA have changed over the historical record. Attribution of such changes gets tricky given the natural variability on decadal time scales. The global climate models as a group are suggesting that the future climate of WA will include wetter winters and drier summers in an overall sense, and so you will want to check this space down the line, say 30 years from now, to see if those projected changes are coming to fruition.