Whipsaw: From an Exceedingly Warm October to a Cold November 2022

As described in this newsletter, WA state experienced unseasonably cold temperatures in November 2022 after record warm temperatures in the previous month. OWSC has received a variety of inquiries about the rapid transition from summer to winter this year. Folks are curious whether there is precedent for such a marked change in temperatures from one month to another, and how the magnitude of this kind of variability is trending. Let’s take a look.

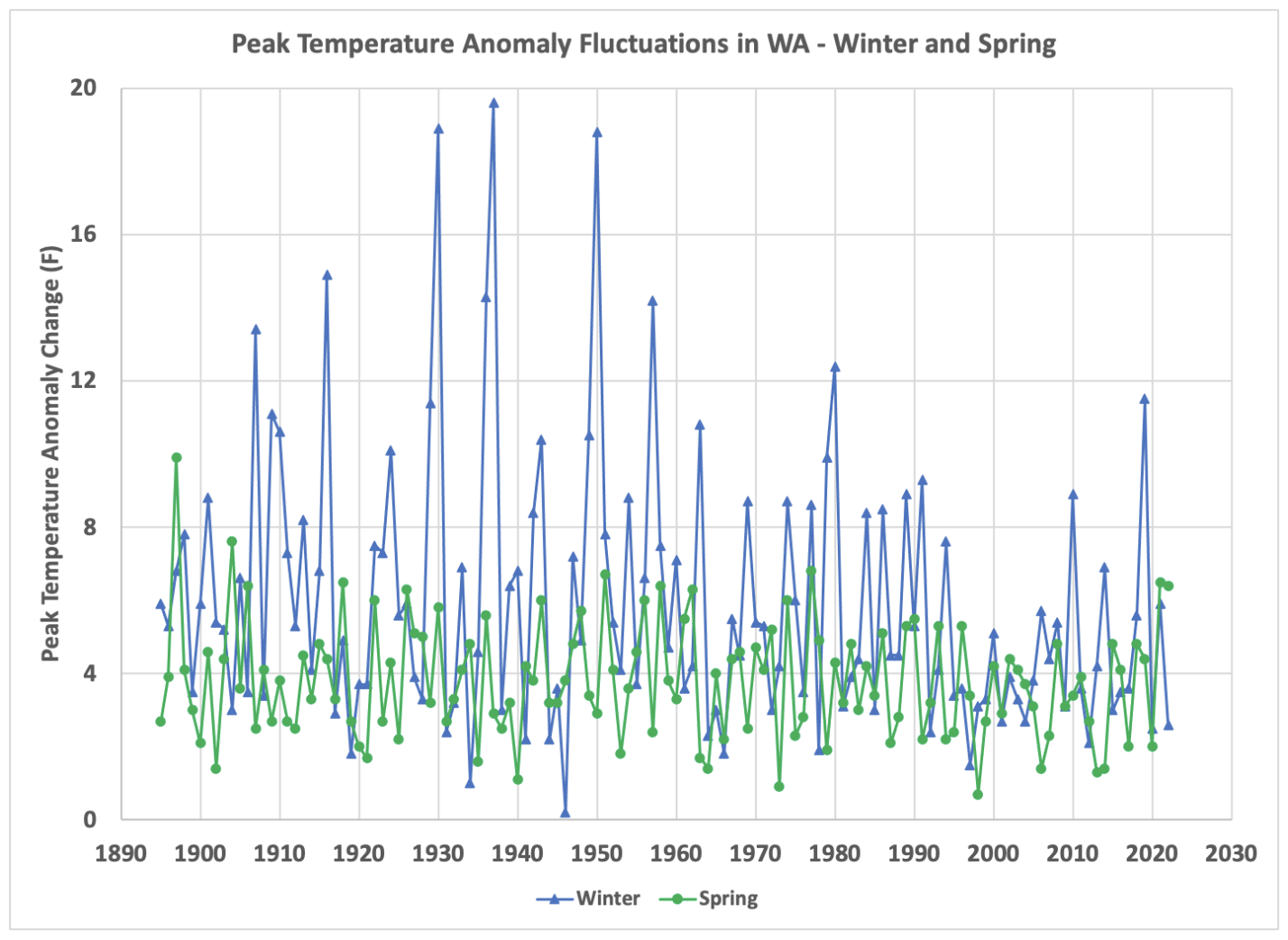

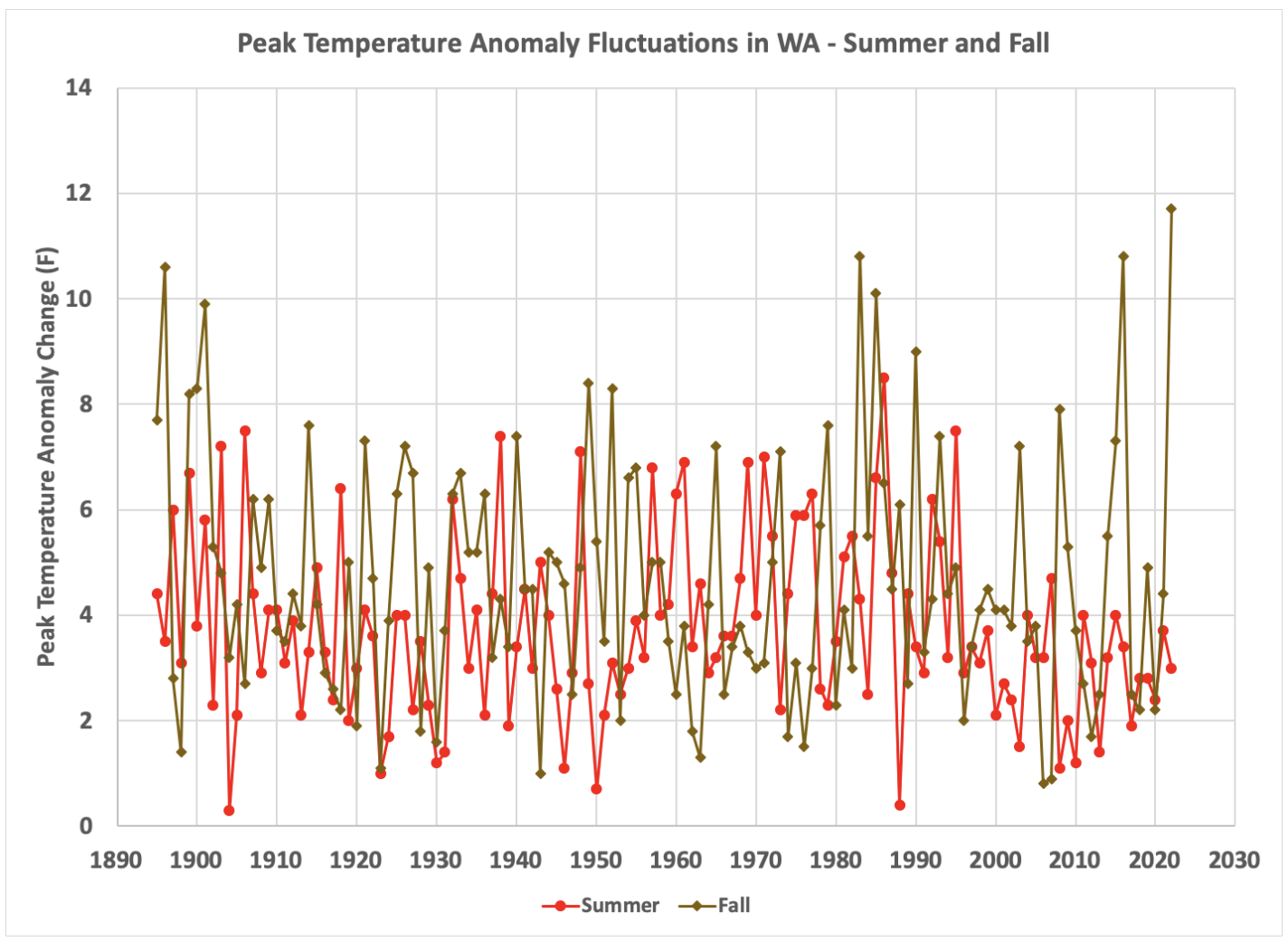

Our specific interest here is to describe how the month-to-month fluctuations in WA statewide temperature anomalies have played out over the historical record. One feature of the climate of the state is the relatively rapid decrease in mean temperatures during the fall, compared to the slower rise in temperatures in spring, which is more or less drawn out over the months of March through June. So here the emphasis is on the fluctuations about the mean annual cycle, which is why we consider monthly mean temperature anomalies using a climatology based on the 30-year period of 1991-2020. The source of temperature information is NOAA’s Climate at Glance, from which time series of statewide temperature anomalies were extracted for each month of the year over the interval of 1895-2022. Our analysis involved simply computing the absolute values of the month-to-month changes in statewide temperature anomalies, lumping them by season, and computing the greatest one-month difference for that season and year. In other words, if March of a given year was 4°F below normal and the following April was 4°F above normal, that would be a monthly temperature change of 8°F. Time series of those absolute values of the greatest changes over the years are plotted for winter and spring in Figure 1, and for summer and fall in Figure 2.

The greatest values of these fluctuations tend to occur in the winter season (Dec-Jan, Jan-Feb, and Feb-Mar). The extreme values all occur in the first half of the record during which there were a handful of bitterly cold Januarys, with anomalies of about -17 to -19°F, bracketed by months with much more typical temperatures. The last really cold January for WA occurred in 1979 with a statewide temperature anomaly value of -13.1°F. The much more recent big swing in winter is represented by the change in anomalous temperature from +2.3 to -9.2°F from January to February 2019. As an aside, the cold weather during the late winter of 2019 coincided with weak-moderate El Nino conditions, which in some ways makes it even more remarkable. Figure 1 also shows that the month-to-month swings in temperature in spring (Mar-Apr, Apr-May, and May-Jun) are quite modest relative to winter. The last two years have included relatively large values, namely the change from -0.2 to +6.3°F during May to June 2021, and the change of the other sense from +1.7 to -4.7°F during March to April of 2022. Both the winter and spring time series suggest a very weak tendency for declining variability with time but it is highly doubtful these trends are significantly different from zero (we have not bothered to compute their statistical significance).

The time series of the temperature fluctuations for summer (Jun-Jul, Jul-Aug, and Aug-Sep) and fall (Sep-Oct, Oct-Nov and Nov-Dec) are shown in Figure 2. Note the change in vertical scale compared to Figure 1; the peak fluctuations during each summer are of comparable value to those of spring. Their magnitudes during the fall are generally somewhat greater, but still considerably less than that during the winter. The transition from +6.6 to -6.0 °F from October to November 2022, i.e., a change of 12.6°F does represent an all-time record for the fall season. Tied for second place are two relatively recent years, 1983 and 2016, during which warm Novembers were followed by cold Decembers. Still, there doesn’t appear to be systematic change in fall temperature variability. The summers of the last 25 years or so have included relatively small fluctuations, but just as for winter and spring, it would be difficult to make the case that this measure of the variability has systematically changed over the record. But we can still marvel at how fast the weather cooled during the past couple of months, and hope sometime before too long, that we have another substantial switch of one sense or the other.