What’s Next for the Pacific Northwest?

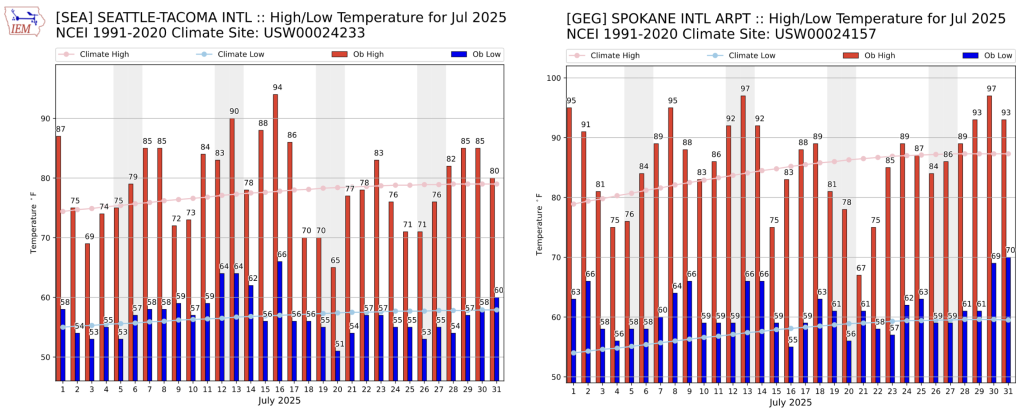

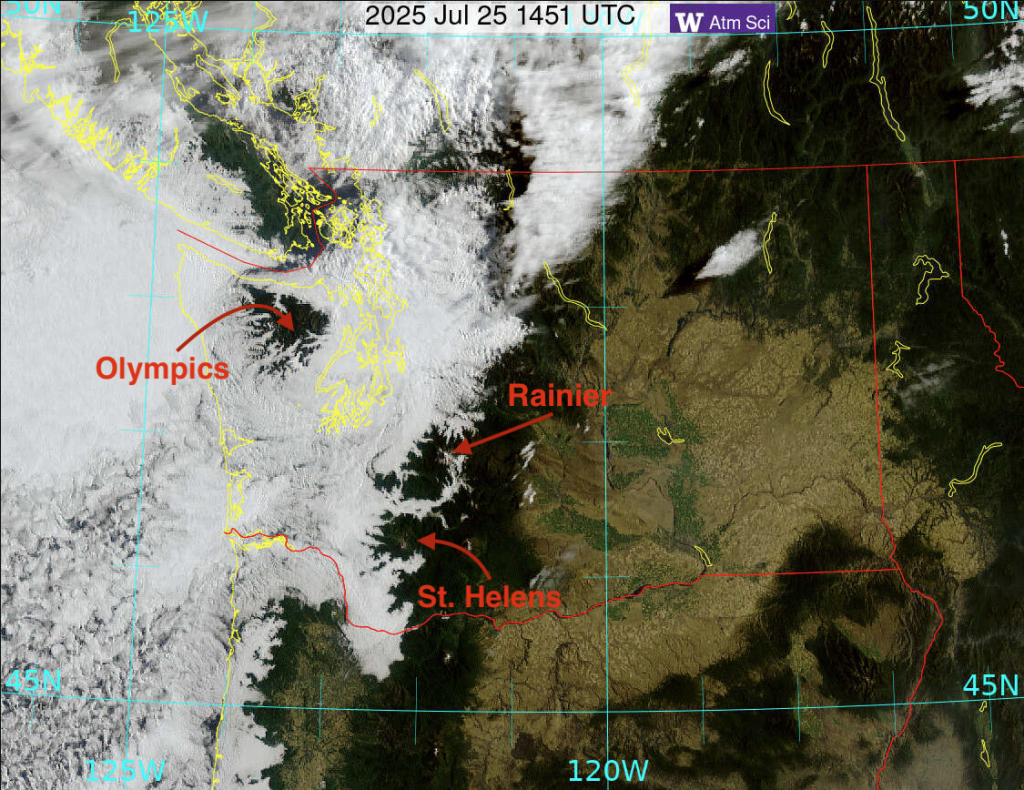

Short Term: Persistent Heat Likely Through Early September

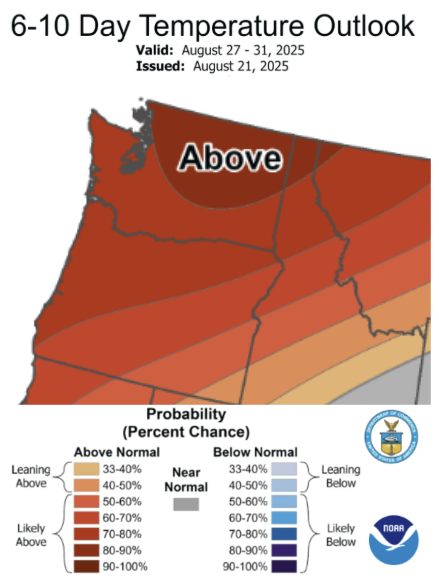

Dangerous heat is building across the Pacific Northwest this week and into the weekend. Warmer than normal temperatures are also expected to persist over the next couple of weeks, as illustrated in the Climate Prediction Center 6-10 Day Temperature Outlook below. There is a 70-90% chance of warmer than normal temperatures from August 27-31, 2025 across the state. Above normals temperatures are expected to continue through at least the first few days of September 2025.

Expect periods of impactful late-summer heat through this period, and consult National Weather Service forecasts, watches, and warnings for up to date current information and local forecasts.

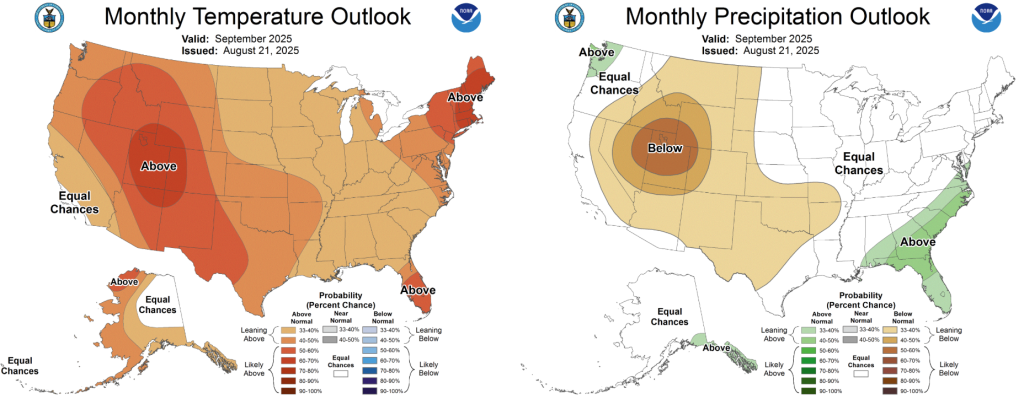

Warm conditions are likely September through November statewide with a slight chance of wetter than normal conditions across western Washington

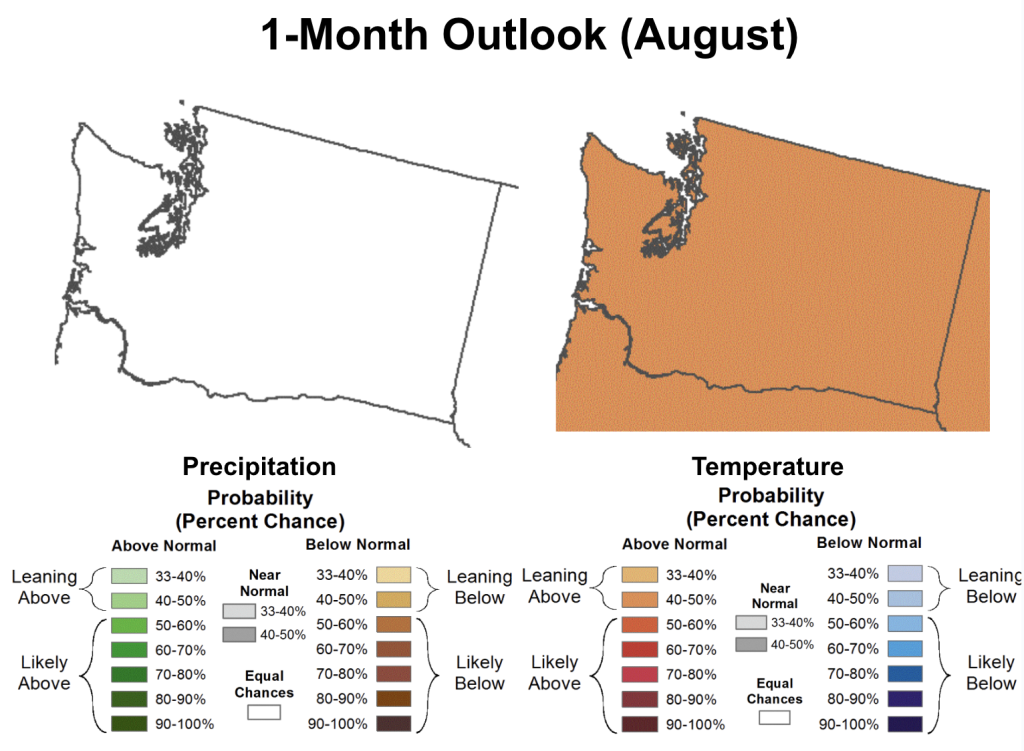

The Climate Prediction Center’s monthly outlook for September 2025 shows elevated chances of warmer than normal temperatures with a slight lean toward wetter than normal conditions across western Washington. Temperatures are most likely to be above normal (50-60%) across the far southeastern corner of the state with a slightly lower chance (40-50%) of above normal temperatures across the rest of the state.

Much of the state is expected to have near normal precipitation in September, but western Washington has a slightly higher chance (33-40%) of wetter than normal conditions. This is due to a more active pattern in mid-range climate models that tends to allow for some early season precipitation to work its way into the state from the Pacific.

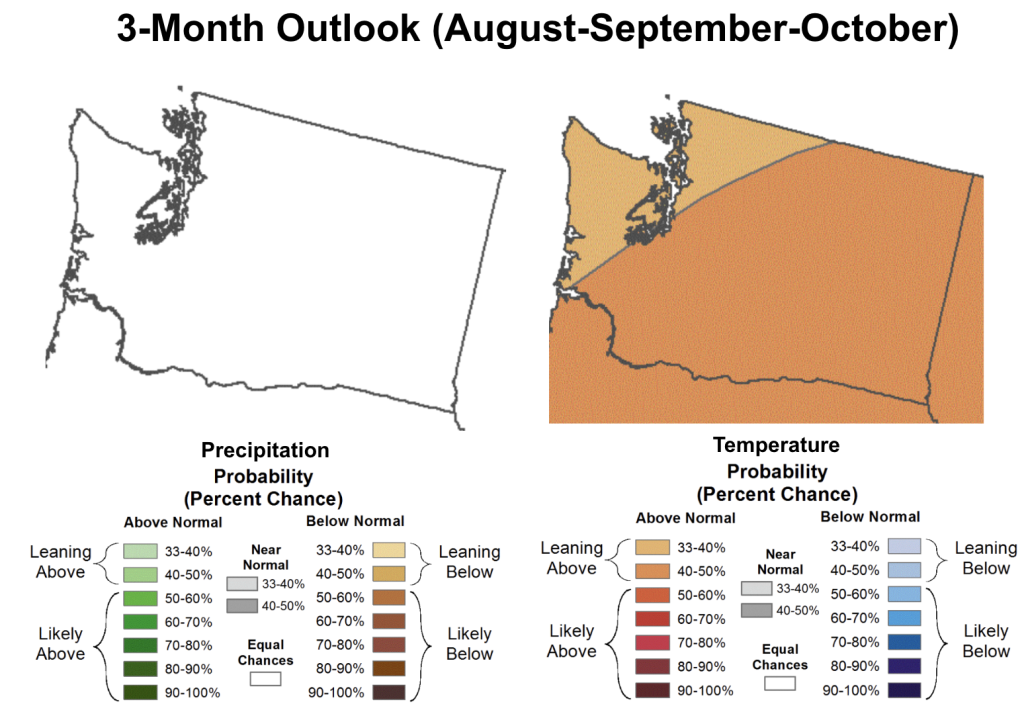

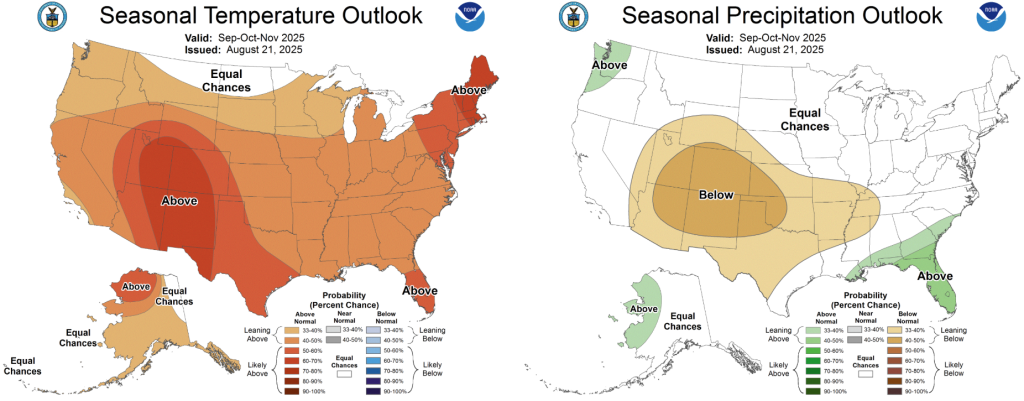

Looking out a bit further, the seasonal forecast for September through November paints a similar picture. Statewide, there is a slight chance (33-40%) of above normal temperatures although chances of warmer conditions are much higher across the interior west, southern, and eastern United States. As for seasonal precipitation, there is a slight chance (33-40%) of above normal precipitation across the western half of Washington as we enter the cool and wet season. This is largely driven by the expected development of a weak and brief La Niña event this fall and winter, discussed below.

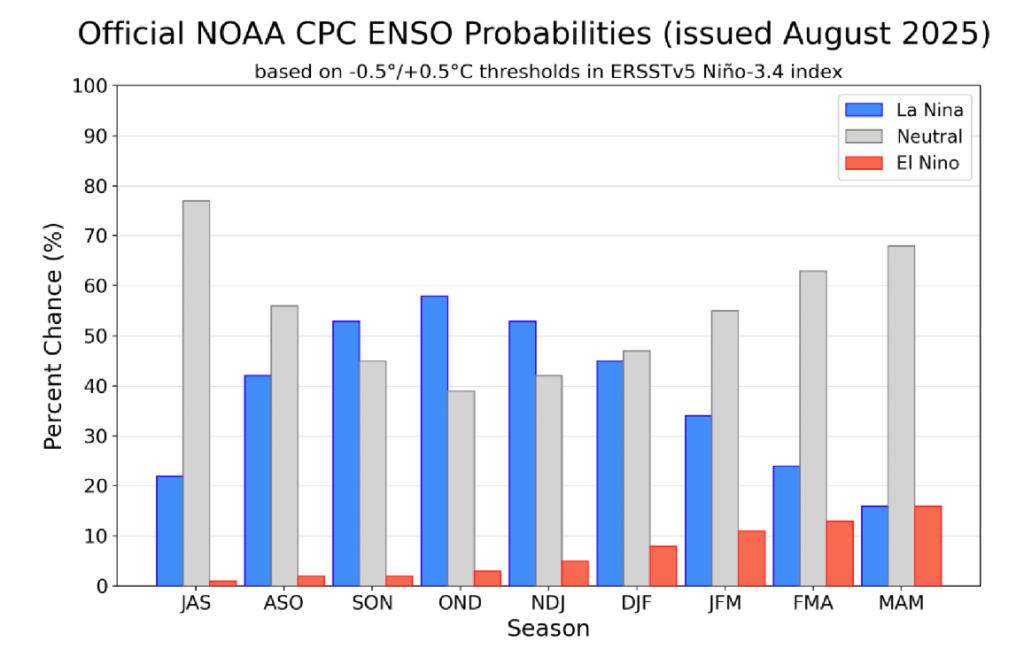

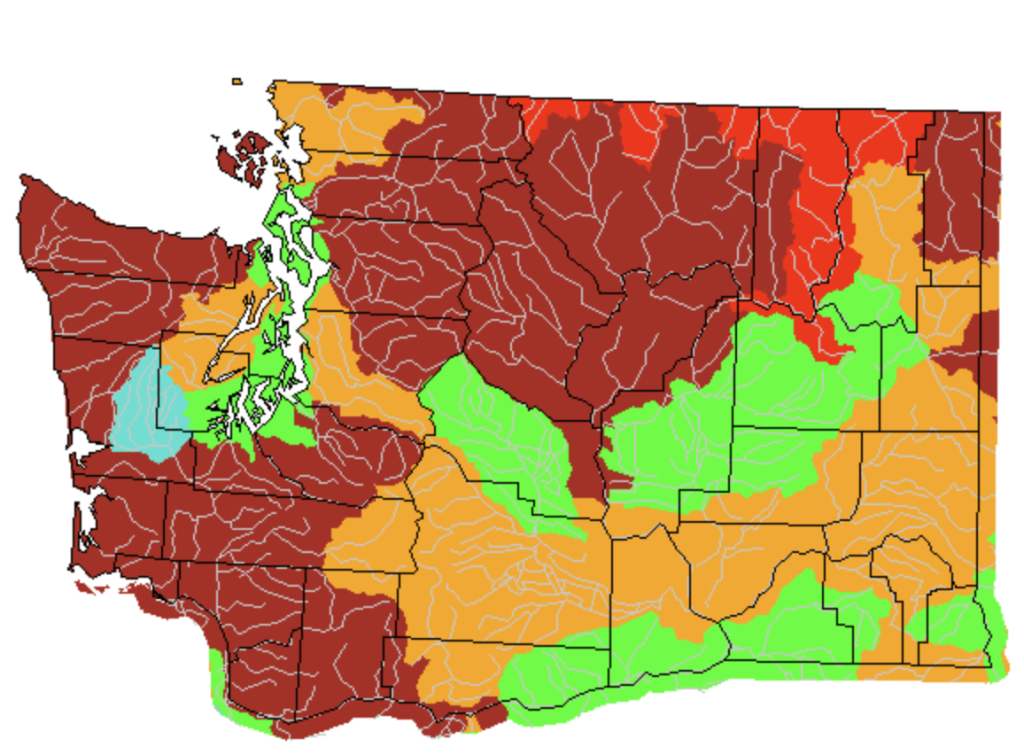

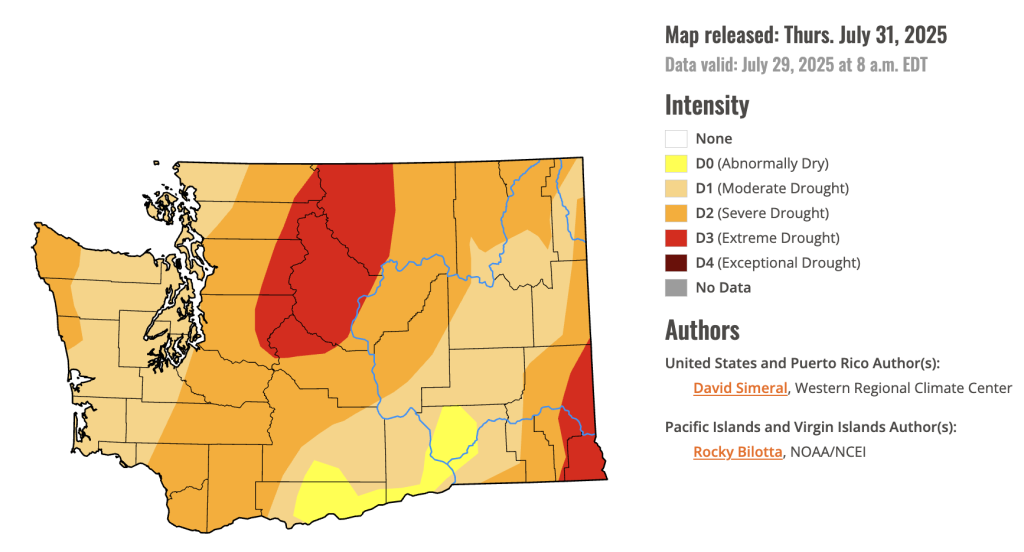

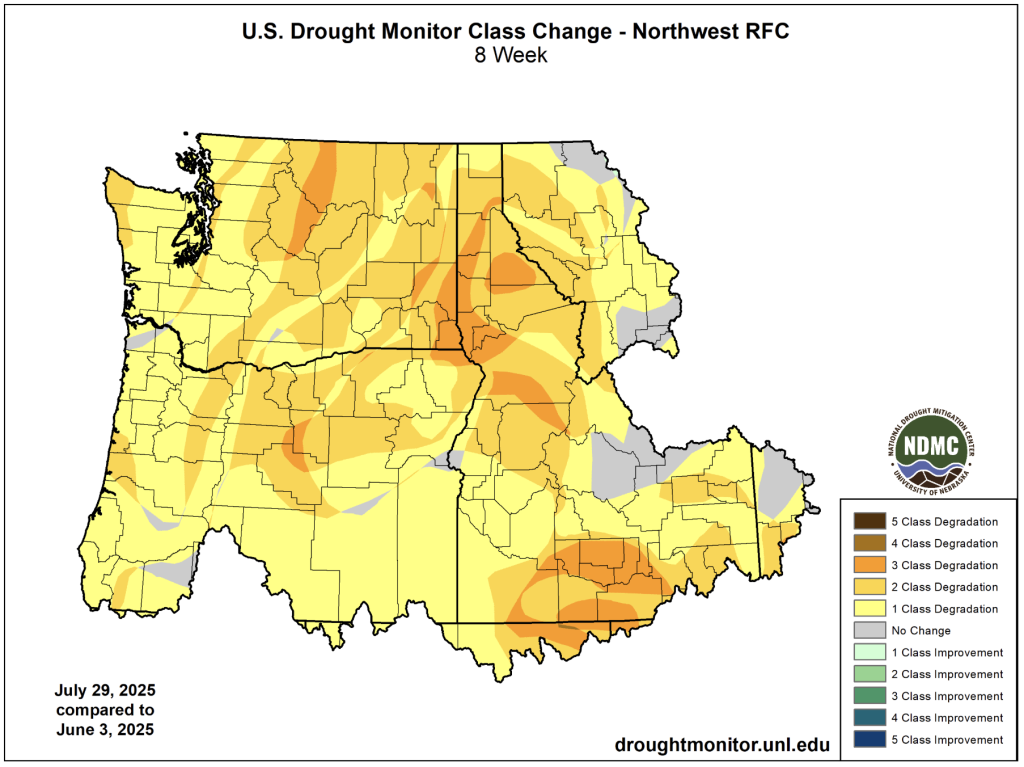

La Niña watch issued for Winter 2025-2026

The Climate Prediction Center/NWS has issued a La Niña Watch for the upcoming cool season, indicating that conditions are in place for the development of La Niña conditions in the Tropical Pacific sometime over the next several months. This La Niña event is expected to be similar to last year in that it will be a rather weak and brief event with conditions likely returning to neutral status by late winter or early spring. There is now around a 55-60% chance of La Niña conditions by early winter, around a 40% chance of neutral conditions, and a less than 5% chance of El Niño conditions. Like all years, natural year-to-year variability remains larger than the influence of ENSO on our regional climate, but La Niña conditions tend to coincide with slightly cooler and wetter than normal conditions for the winter season. This is cautiously optimistic news considering the level of Severe to Extreme drought currently gripping the state.