By Nick Bond

Many regular readers of this column are aware of the effects of La Niña, and variations in the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) in general, on the overall weather of the Pacific Northwest during the cool season. Nevertheless, it bears repeating that La Niña is often (but not always!) accompanied by relatively cool and wet winter weather in an overall sense, and a healthy snowpack going into spring. And some of you have also probably heard that it is more likely than not that a weak La Niña will develop in the next couple of months or so. Zooming out, you might have noticed that many of our recent winters have included cool/La Niña conditions in the tropical Pacific. Here we explore the extent to which that is the case, and some of the research on the factor(s) that could explain the observed tendencies in ENSO.

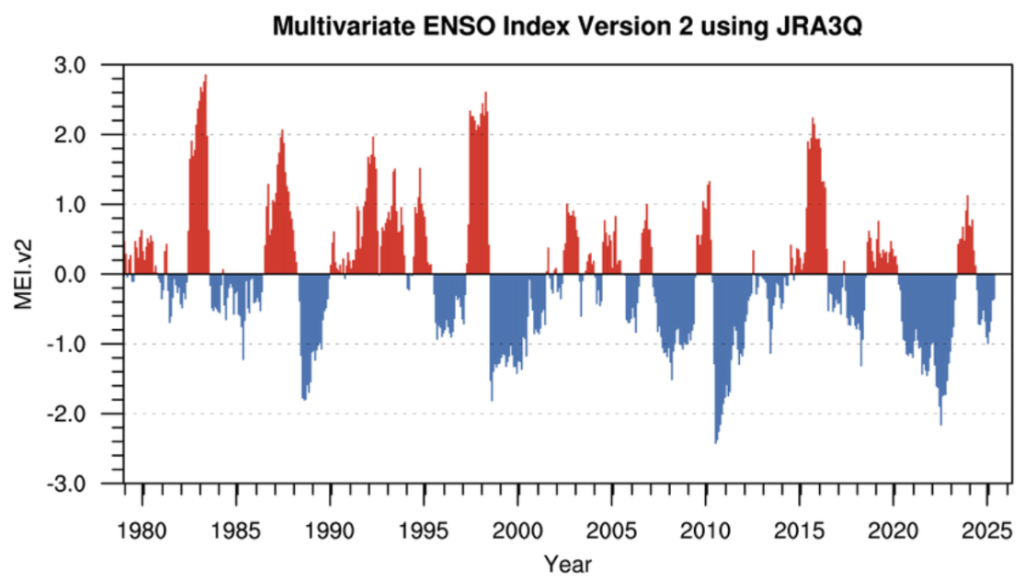

There are a variety of ENSO indicators. For a first look we can use the multivariate ENSO Index Version 2 (MEI.v2, from NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory) to describe the state of ENSO since 1980 (below). Note the preponderance of negative (cool) conditions in the tropical Pacific since the late 1990s. There have been some warm periods during that interval, but with the exception of 2015-16, the warm (El Niño) events have been of only moderate magnitude. The asymmetry shown in Figure X (more La Niñas, fewer El Niños) is also present in the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI), which is calculated based on sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies (ONI is used by NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center in the declaration of La Niña and El Niño events). Is it merely a coincidence that we’ve been having more La Niña events? After all, the climate system does have intrinsic variability on multi-year time scales. Or is it instead an indication of a lasting trend?

Multivariate ENSO Index Version 2 (MEI.v2) from January 1979 through May 2025 as provided by NOAA/PSD

Multivariate ENSO Index Version 2 (MEI.v2) from January 1979 through May 2025 as provided by NOAA/PSD

Systematic trends in the occurrence of La Niña versus El Niño in the tropical Pacific would have impacts on the Pacific Northwest. There has been plenty of discussion about how ENSO is likely to play out over future decades, and we are limited by short and imperfect historical records and complex interactions with the larger climate system (Karamperidou et al. 2020). Adding to the challenge, Wills et al. (2022) show that the suite of global climate models as a group do not reflect this preference for La Niña events, nor the associated effects on the atmospheric circulation over the North Pacific and western North America.

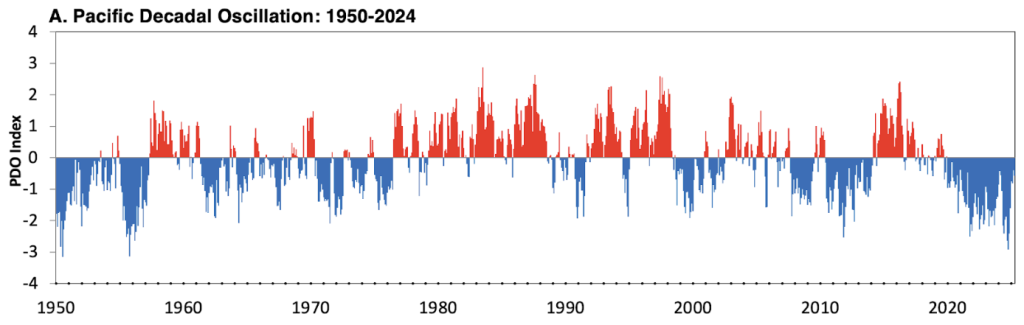

ENSO is related to the slower-moving Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), which describes the most notable pattern of SST variability in the North Pacific. Living up to its name, the PDO features prominent fluctuations on multi-year or even decadal time scales. While the PDO index is based on ocean temperatures, it is associated with a variety of atmospheric and environmental impacts through a combination of causes and effects. From this corner’s perspective, it is especially important to note that negative values of the PDO tend to be accompanied by cool and wet winters in the PNW, while the opposite is true for positive values. For example, relatively frigid weather occurred in the PNW during a period of negative PDO values in the early 1950s, with essentially the opposite happening in the early 1980s. The PDO has been in a strongly negative state recently (as illustrated below) and new research has suggested that these conditions may be linked to warming (Klavans et al. 2015) and continue into future decades (Todd et al. 2025). These results are based on new methods of analysis applied to climate model simulations, and new reconstructions and simulations of the past climate, respectively. Both studies point out that global climate models tend to underestimate atmospheric-ocean coupling in the North Pacific, and the overall response of the North Pacific atmosphere-ocean system to global warming. In other words, models are not capturing some of the very processes that drive PDO and ENSO variability.

Monthly values of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) from 1950 through 2024.

Monthly values of the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) from 1950 through 2024.

If the tendencies towards negative states of ENSO and the PDO continue into the future, and that is a big if, it is mostly good news for WA state. Conceivably that could offset some of the warming ahead, and in particular help defray reductions in our winter snowpacks, and overall heating of our landscape and regional waters. But we don’t know if their recent tendencies will prevail. The climate system seems to always have some tricks up its sleeve. At least for the winter ahead, here’s hoping there are not any rude surprises.

Karamperidou et al. (2020) https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119548164.ch21

Klavans et al. (2025) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09368-2

Todd et al. (2025) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01726-z

Wills et al. (2022) https://doi.org/10.1029/2022GL100011