Sea Level Rise Projections and Visualizations

On October 31st, the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) began in Glasgow, Scotland. There, the parties to the Paris Agreement are expected to ramp up their commitments to reducing greenhouse gas emissions so that the world may prevent some of the worsening effects of climate change. In this month’s spotlight, we hope to give our readers an idea of what tangible impacts these decisions may have on Washingtonians by discussing predictions of sea level rise on our coast under different emissions scenarios.

Global average sea levels are rising because of increasing global average temperatures. There are multiple mechanisms behind sea level rise, with some being more obvious than others. The most important cause is the melting of ice. Although its disappearance will be harmful for other reasons, sea ice won’t contribute to sea level rise – only ice that resides on land, like glaciers, will. Most of the potential for sea level rise via meltwater comes from the ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica. If all the ice on Greenland were to melt, we could expect 24 feet of sea level rise (IPCC); if all the ice on Antarctica melted, we could expect 191 feet of sea level rise (Winkelmann et al. 2015). Complete melting of either the Greenland or Antarctic ice sheets won’t happen any time soon, but the longer we wait to rein in greenhouse gas emissions, the greater and fast the melt.

Since 1880, global average sea level has risen between 8 and 9 inches, but most of that has not come from the melting of the ice sheets. For now, sea level rise mostly comes from the melting of glaciers as well as a process known as thermal expansion. As human-caused greenhouse gas emissions warm the atmosphere, so too do they warm the ocean. Warm water takes up more volume than cold, dense water. This is the same phenomenon observed in mercury thermometers; the red mercury rises as temperature increases. This increase in ocean volume rather than mass contributes a significant amount to sea level rise.

There are many other local factors that may affect sea level rise. Smaller contributors include the construction of man-made water reservoirs, groundwater extraction, ENSO events, and the change in gravitational pull of glaciers and ice sheets as they melt. One of the most important factors for determining future sea level rise across Washington’s coastlines is local trends in land elevation. Land sinks and rises in response to the movements of tectonic plates. This can either amplify or offset other changes in sea level rise.

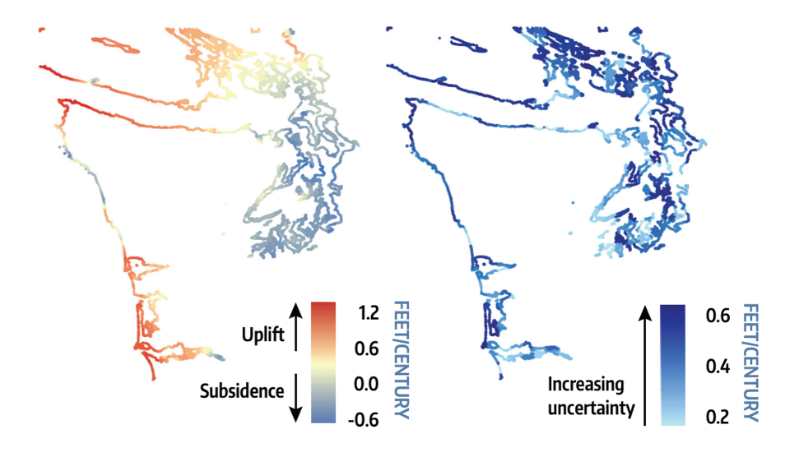

In 2018, the Climate Impacts Group’s Washington Coastal Resilience Project released the Projected Sea Level Rise for Washington State assessment to provide state leaders the tools and information needed to prepare for future sea level rise. The assessment created estimates of uplift and subsidence along all of Washington’s coastlines to factor into their estimates of future sea level rise. As seen in Figure 1, Washington’s coastlines are not universally experiencing uplift or subsidence.

Some parts of Washington, like the Puget Sound area, are sinking at rates slower than half a foot per century. The majority of Washington’s coastlines farther west are actually rising. In some places, the uplift is to the tune of a foot or more per century. This uplift will not be enough to offset sea level rise entirely, but it will prevent the impacts of sea level rise from being worse. On the contrary, the subsidence in the Puget Sound region will worsen these impacts.

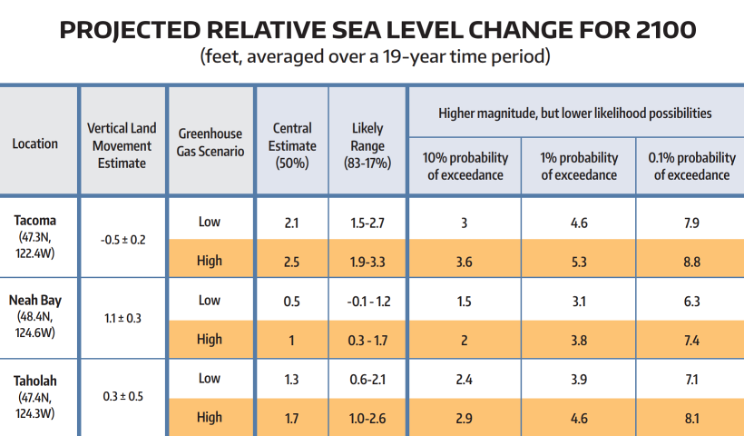

Table 1, taken from the assessment, provides estimates of sea level rise for three different locations along Washington’s coastlines for both low and high emissions scenarios. The first location, Tacoma, is experiencing subsidence, and as a result is projected to see the most sea level rise of the three. In a low or high greenhouse gas emissions scenario, the report gives a 50% chance for more than two feet of sea level rise by 2100. In contrast, Neah Bay, which is experiencing uplift, has a 50% chance of seeing a foot of sea level rise by 2100 under a high greenhouse gas emissions scenario. That is less than half as much sea level rise as is predicted for Tacoma under the same conditions. Under a low greenhouse gas emissions scenario, Neah Bay has a 50% chance of seeing just half a foot of sea level rise. Taholah is experiencing very little vertical movement, and as such, its sea level rise projections lie somewhere between Neah Bay’s and Tacoma’s. The Washington Coastal Resilience Project published interactive online tools alongside the assessment so that anyone may gain a better understanding of sea level rise projections for 171 different locations along Washington’s coast.

Why does sea level rise matter? About 40% of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometers of the coast. According to NOAA, nearly 70% of Washingtonians live in coastal regions. Most prominently, portions of these regions and peoples will be subject to more frequent and costly flooding, but there are plenty of impacts from sea level rise that aren’t so obvious. Coastal bluffs and shorelines will be subject to erosion, changing the very shape of our state. Importantly, these coastal areas are of the utmost importance to the Indigenous tribes that have inhabited the regions for generations; sea level rise may destroy their ancestral homes. Low-lying land areas will be subject to saltwater intrusion with implications for agriculture, and marine ecosystems will also be impacted by changes in estuaries, tidelands and other crucial nearshore habitats. Washington’s economy relies heavily on the health of these ecosystems and communities; not only are flood damages costly, but so too are the losses from reduced tourism, impacts on fisheries and ecosystems, and aquifer contamination.

Sea level rise is just one example of why the decisions we make today have lasting implications for the future. For the three locations listed in Table 1, the difference between a low or high greenhouse gas emission scenario is about half a foot of sea level rise. At the time this newsletter is published, world leaders are gathered in Scotland determining the future for generations of Washingtonians to come. Every emissions reduction pledge from every country has implications for nearly 70% of Washingtonians’ backyards and communities from a sea level rise perspective alone. The other 30% are impacted just as much through lenses of heat waves, fires, or other climate changes. Will our state look back at the efforts of leaders at COP26 and think it was enough? Only time will tell.