Are Springs Becoming Rainier in Washington State?

It has been a wet spring in Washington state. The second half of May 2017 has actually been dry but that does not really make up for the drenching from March through mid-May. The wet weather was not just an inconvenience but represented some real issues for various sectors, notably agriculture in eastern WA. Whenever the weather is odd, which is much of the time, the Office of the Washington State Climatologist is asked why, and often whether climate change is responsible. The answer is usually “No”. But in this case a glib answer is insufficient.

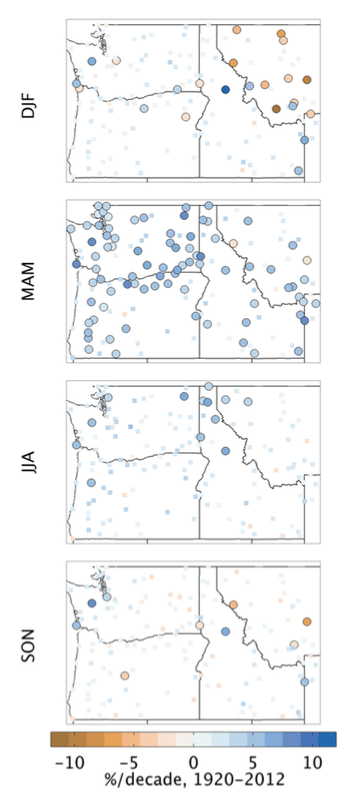

respectively, with the color scale at the bottom. Reproduced from Abatzaglou et al. (2014).

There does seem to be an overall trend towards wetter springs, specifically the months of March through May, in the Pacific Northwest. This is documented in Abatzaglou et al. (2014), which used station data to evaluate overall seasonal trends in temperature and precipitation for the years of 1920 through 2012. Figure 1 shows the mean trends in precipitation for the four seasons; note that spring has by far the most systematic signal over the years of 1920-2012. Because memories can be short (remember the dry spring and drought of 2015?) and precipitation has a great deal of inherent variability, we thought it might be interesting to pursue the subject a bit further.

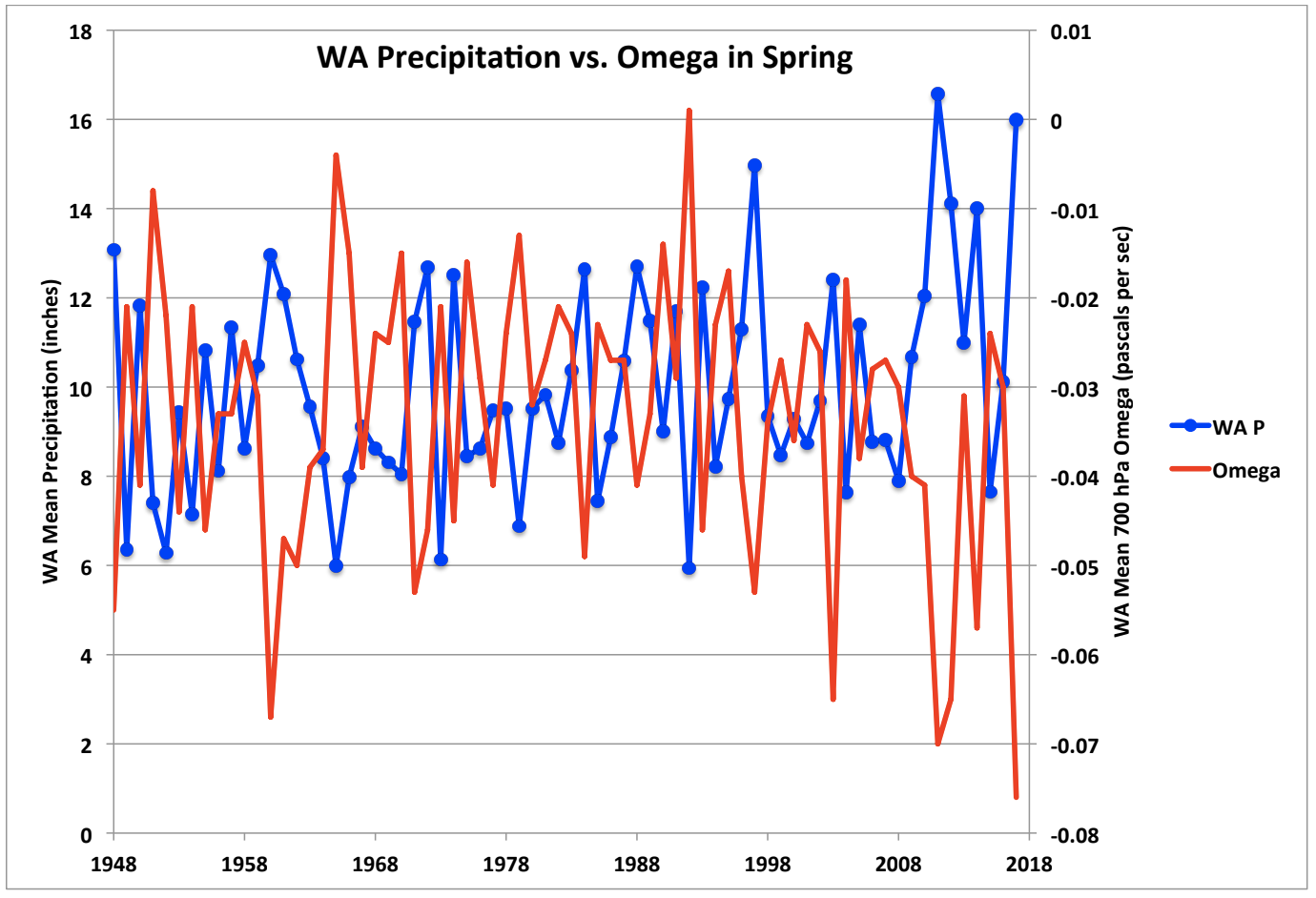

The approach taken here is to consider the year to year variations in spring precipitation for WA as a whole. The time series shown in Figure 2 was extracted from NOAA’s Climate at a Glance web site (https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/time-series), for the years of 1948 through 2017. The most obvious characteristic of this time series of precipitation is its large interannual variability. There is an upward trend, with the linear fit indicating an increase of a bit more than 2 inches over the 70 years. In general, the last couple of decades have had the wettest springs and none of the really dry years. OK, so it looks like it has gotten wetter, but why?

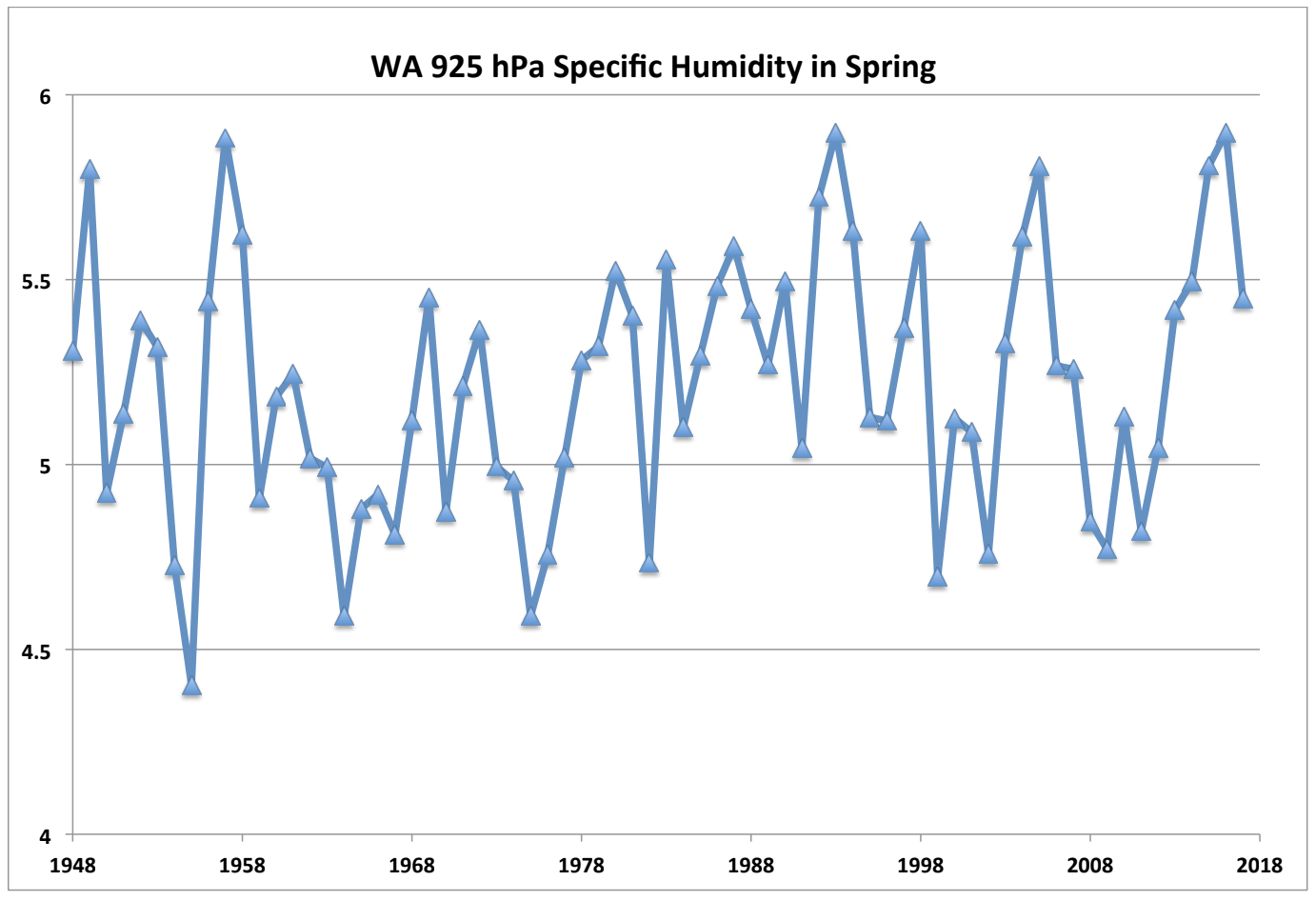

There are two possible ways this happened and that is through the dynamics or the thermodynamics, or some combination thereof. In other words, has the increase in precipitation been due more to greater upward motion or to higher atmospheric moisture contents? A rigorous assessment of this issue is way beyond the scope of the present piece, but thanks to atmospheric reanalyses, it is straightforward to arrive at some tentative conjectures. Towards that end, we considered time series of a few atmospheric parameters that could plausibly be linked to precipitation. An obvious one is the vertical velocity itself; plotted in Fig. 2 is a time series of the mean omega at 700 hPa for March through May for WA from the NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis. Negative values of omega mean upward motion and it is evident that the year to year variations in precipitation strongly correspond with those in omega (the correlation coefficient is about 0.86), as they should. In addition, there is a trend in omega towards decidedly more negative values (upward motion) during the last 20 years or so amidst large interannual variations. A somewhat different result was found with respect to atmospheric humidity. Figure 3 shows the time series of specific humidity for WA state at the 925 hPa level, which represents a measure of atmospheric boundary layer moisture content. The year to year values in this parameter have essentially zero correlation (r ~0.03) with corresponding mean precipitation totals. But there is a positive trend with time, with the linear fit equivalent to an increase of about 0.24 g kg-1 over the 70-year period. Based on a scaling of the terms in the seasonal mean moisture budget, it appears that the increase in precipitation can be attributed primarily to the change in vertical motion, with the increased water vapor content playing a secondary role. We hasten to add that a much more thorough analysis would be required to establish that result with confidence. A continuation of higher atmospheric moisture contents seems likely as the climate warms. So unless the dynamics become less favorable in the future, which is quite possible, we should expect more wet springs. All the more reason to celebrate rather than curse the rain.

Reference:

Abatzoglou, J., D. Rupp, and P. Mote, 2014: Seasonal climate variability and change in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. J. Climate, 27, 2125-2142, doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00218.1.