Climate Change and Our Natural Resources: A Report from the Treaty Tribes in Western Washington

A group of twenty member tribes of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission (NWIFC) recently released a report detailing how climate change is apt to impact the ocean, freshwater and terrestrial systems of western Washington. Readers of this newsletter are encouraged to check out the report at the following website: http://nwtreatytribes.org/climatechange/. There have been a variety of efforts of this type, so why this recommendation?

The tribal perspective is unique and valuable. It discusses the myriad ways through which the evolving climate, along with other environmental changes such as logging and development, are impacting the livelihoods and cultures of the native people of our region. It includes a thoughtful discussion of how traditional knowledge can be used in conjunction with scientific practices such that cultural differences are acknowledged and respected. Importantly, it includes examples of adaptation efforts being carried out to minimize the impacts of present and future changes. For example, the Lummi Nation is improving the habitat of the estuary of the Nooksack River through replacement of invasive with native species and restoration of tidal circulations. And the report actually concludes on a positive note, suggesting the opportunities that change can bring.

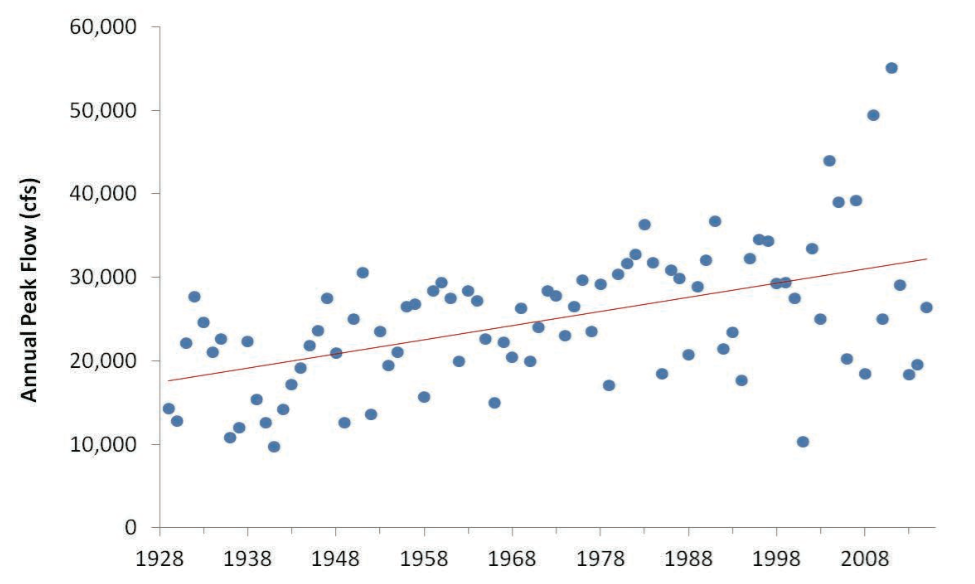

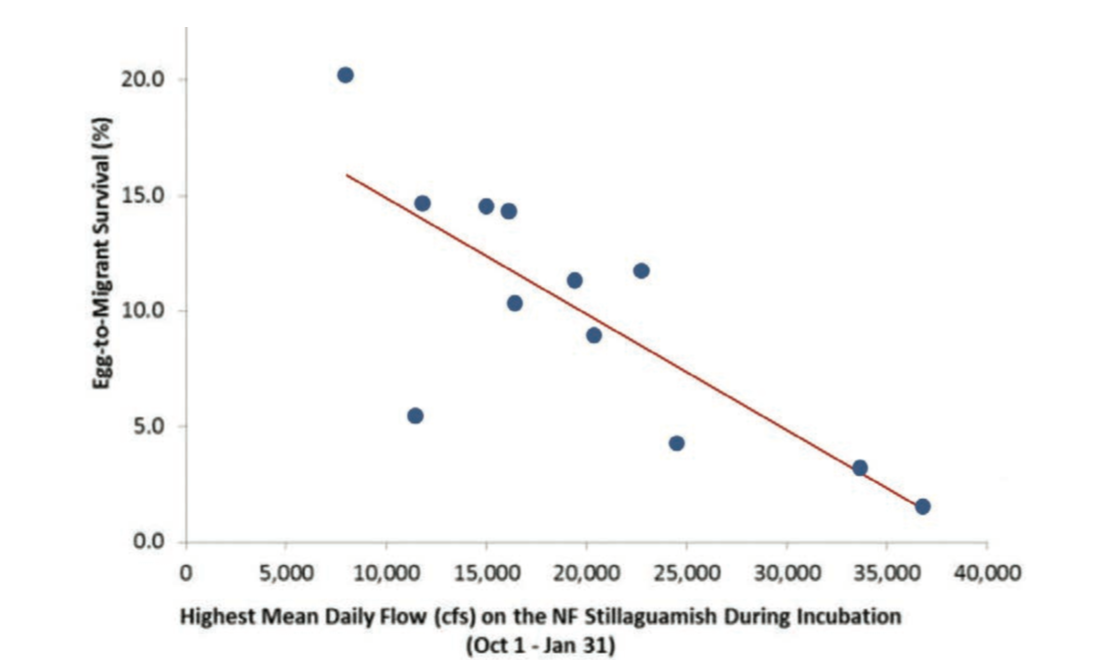

It is emphasized that the report has solid scientific underpinnings with hundreds of citations. For instance, we reproduce here a pair of figures from the report related to the Stillaguamish River. Our readers may already know that many regional streams are experiencing an observed trend of greater daily peak streamflows (floods), including the Stillaguamish River (Fig. 1). What may not be as fully appreciated are the effects of these floods on salmon. On many streams, minor to moderate floods at regular intervals help rejuvenate spawning beds or redds. But big floods tend to silt up or even destroy redds, resulting in reduced viability of salmon eggs. This effect has been documented on the Stillaguamish (Fig. 2), and is of substantial concern given the expectation of heavier wintertime rains in our mountains and hence more severe floods. Other examples of threats associated with the future climate are presented. In general, this document represent a valuable resource on regional climate change and in particular its impacts on our waters and landscapes.

The report reflects the contributions by many individuals associated with western Washington tribes, and was compiled by Eliza Ghitis, a climate scientist with the NWIFC. We encourage our readers to check out this document, which will help guide addressing the challenges ahead associated with the future climate.