The Spring Transition in the Winds Along the WA Coast and its Effects on the Coastal Ocean

There is a seasonal cycle in the prevailing winds along the coast of Washington state. Winter winds are generally from the southwest, with considerable variability due to the passage of storms, and summer winds are generally from the northwest, with intermittent periods of southerlies. Oceanographers call the switch in the winds the “spring transition”, and it has important consequences for the coastal ocean.

The flow in the upper ocean occurs to the right of the wind in the Northern Hemisphere due to the earth’s rotation. This effect, known as Ekman transport, causes onshore-directed flow in conditions of southerly winds along the Washington coast, and off-shore-directed flow during northerlies. Since the lateral movement of water is restricted by the coastline, onshore-directed flow induces downwelling in the coastal zone, while offshore-directed flow induces upwelling. A review of this mechanism is available at the following website: http://oceanmotion.org/html/background/upwelling-and-downwelling.htm. This is a matter of much more than just academic interest.

The chemical properties of the water in the coastal zone are strongly dependent on whether there is downwelling or upwelling. The water at depth tends to feature relatively high concentrations of nutrients such as nitrate and phosphate that are essential for the growth of phytoplankton, and a low concentration of dissolved oxygen. This water can be brought close to the surface during upwelling and serves to sustain photosynthesis, i.e., the growth of phytoplankton supporting the food web. For this reason, regions of coastal upwelling generally support very productive fisheries and large populations of seabirds and marine mammals.

Information on present and past upwelling along the US west coast is provided by NOAA’s Pacific Fisheries Environmental Laboratory at https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/. It bears noting that on average, that upwelling is considerably stronger to the south of Washington State. While our beaches tend to be breezy in the summer, their counterparts from south-central Oregon to central California generally experience much stiffer north winds. One might imagine that these beaches would represent delightful places to be on sunny summer afternoons, but that depends on one’s tolerance to getting sandblasted. The upwelling winds to our south of WA are so strong and persistent enough that the coldest sea surface temperatures at the coast occur in the summer rather than the winter!

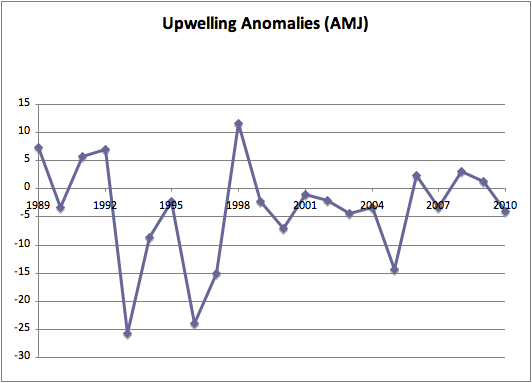

There are variations in the seasonal mean winds along the Washington coast, of course. A time series of an index of the upwelling at 48 N, 125 W near Forks, WA during spring (April-June) is plotted in Figure 1. This time series indicates that the spring upwelling was anomalously weak in the early 1990s and relatively strong from the late 1990s into the early 2000s. Since then most years have been near normal except for 2005. The delayed upwelling that year was particularly pronounced to our south along the Oregon and California coasts, and had profoundly negative impacts on the survival rates of juvenile salmon and the fledgling success of seabirds, along with other marine organisms. As an aside, the summer and early fall of 2006 demonstrated what can happen when there is too much of a good thing. The abnormally strong and persistent upwelling that occurred during that period caused massive die-offs of Dungeness crabs and other species due to the continued transport of water with especially low oxygen content onto the shelf.

The cool and inclement weather of this spring has been accompanied by more southerly winds than usual during the last month or so, and hence a slow start to upwelling season. This has resulted in low phytoplankton levels, as is vividly demonstrated by comparing a map of surface chlorophyll-a concentrations for late May 2011 (Figure 2a) with its counterpart from 2009 (Figure 2b), which had near normal upwelling. There is little indication one way or another about how the weather and winds will play out over the next few months. The onset of consistent northerlies along the coast and upwelling would boost the productivity of the coastal marine ecosystem. Other parts of the state are liable to know that when it happens because those conditions tend to be associated with less rain and more sunshine in the western part of the state and warmer temperatures on the east side. Unfortunately, we cannot anticipate when that should occur since we have little understanding of the causes of climate variations in the Pacific Northwest during the spring into summer. As discussed here, progress on this issue would be particularly relevant for fishers and managers and others with coastal ecosystem interests.