The Timing of Seasonal Closures of Mountain Passes in WA State

Storms are beginning to roll into the Pacific Northwest more or less on cue with the usual start to the wet season. But when is it liable to cool down enough for snow in the high country and hence winter recreation? One way to gauge the timing of the onset of winter is by the dates of the seasonal closures of the North Cascades Highway, and Cayuse and Chinook Passes, and that is what is considered here.

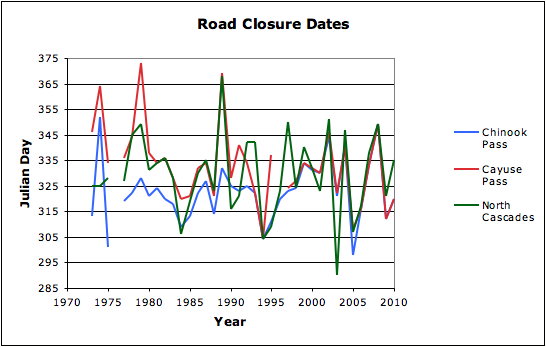

The dates of the closures of the three passes for years of 1973 to 2010 are shown in Figure 1. The mean date of closure ranges from about Julian date 322 (19 November) at Chinook Pass to Julian date 332 (29 November) at Cayuse Pass. The great majority of the years have closure dates between early November and the middle of December; the year-to-year variations in closure dates are on the order of 2 weeks. The three passes tend to act as a group in terms of being closed relatively early or late, as might be expected. The major dumps of snow that are required to raise the avalanche hazard high enough to close these passes are rarely highly localized. A notable year in the record is 1976 where no closure date is plotted on Figure 1 for any of the passes. The passes remained open that winter due to the extremely low snowfall, especially during the early and middle portions. Only 2 years in the record had closure dates that were delayed until January – the 79/80 and 89/90 winters. It is also worth noting that a long-term trend in the closing dates is lacking.

It appears that La Niña conditions will be present in the tropical Pacific through the upcoming winter, which tends to means more snow than usual in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. As discussed in last month’s newsletter, La Niña, and more generally the phenomenon known as El Nino-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), has corresponded more with precipitation amounts early in the cool season (October-December) and temperatures after the first of the year. Does this mean that the passes are liable to close earlier than usual? The answer may be a bit surprising. We compared the closure dates shown above with the mean NINO3.4 index for October through December of each year and found essentially no correspondence for the period of record. There is a weak indication that very late closures are rare during La Niña but that is about it. This lack of correspondence is a good example of how climate-related factors such as ENSO can provide useful indications of seasonal mean weather in a probabilistic sense, but little or no help with regards to timing individual weather events. The winter of 2010-11 nicely illustrates this aspect. For example, there was no way to anticipate going into that season that our best cold-air outbreaks would be in late November and late February rather than during December or January.

These three Cascades passes have striking scenery, and autumn has its special charms. But if you have your heart set on driving these routes this year, the past record suggests it is probably prudent not to wait too long into the month of November. In case you are planning a trip of this sort, you may want to check out the detailed mountain weather forecasts provided by the Northwest Avalanche Forecast Center at http://www.nwac.us/.