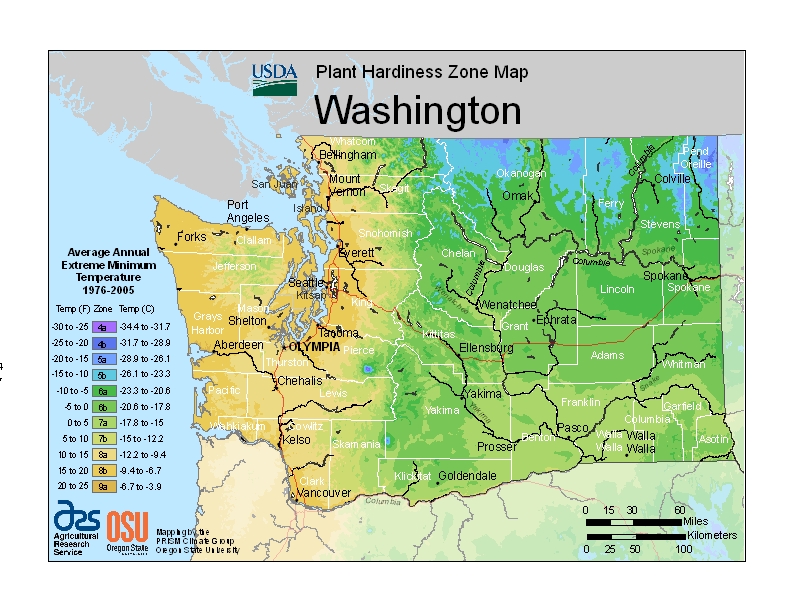

Plant Hardiness Zones for WA State

The US Department of Agriculture has recently posted new plant hardiness information; a map for WA state is reproduced here (Figure 1) and can be found at the following website: http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/. This map indicates the average annual minimum temperatures that can be expected based on the historical record extending from 1976 through 2005, providing guidance as to what types of plants can survive and thrive in a region. The effects of the state’s terrain are evident in a general sense, with much colder extreme temperatures east of the Cascades and at higher elevations. The analysis upon which this map was based was broad-scale in its nature relative to the scales characteristic of the microclimates in various regions of the state. In other words, the utility of this map may be enhanced through account of local effects on minimum temperatures.

The lowest temperatures in WA generally occur during clear, calm weather during arctic-air outbreaks, especially after recent snowfall. These conditions promote nighttime cooling of a shallow layer of air near the surface. This air is relatively dense, and if the winds are light, will tend to flow downhill to collect in low-lying locations. This results in hilltops and slopes often being warmer than valleys in the late-night and early morning hours. The spatial scales of these effects range from less than a kilometer to tens of kilometers and can be impacted by the steepness of the slope. This general rule certainly has some exceptions. In particular, urban areas and locations near bodies of water are not as prone to nighttime cooling, and therefore experience locally warmer minimum temperatures. The type of land use in the surrounding area (e.g., heavily vegetated) can also account for variations in minimum temperature over relatively short distances.

http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/.

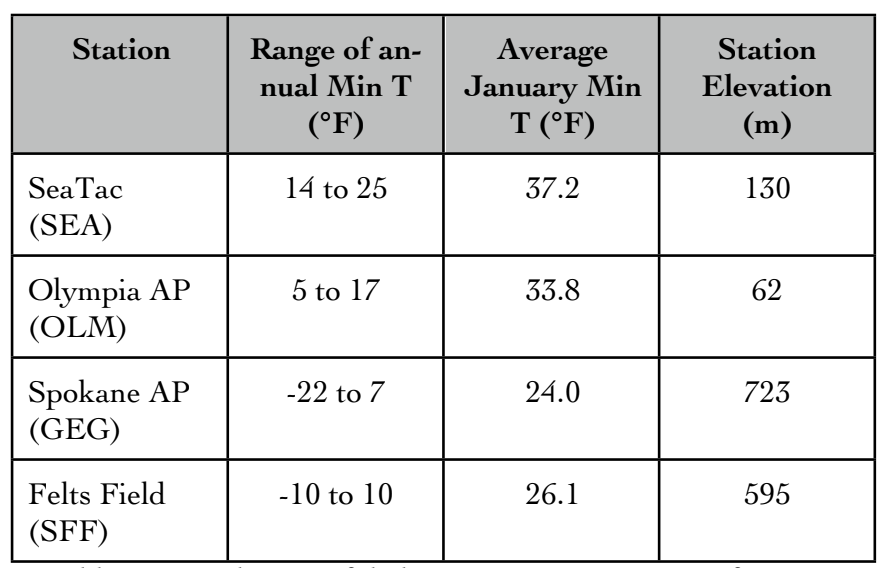

The differences in extreme minimum temperatures might be larger than would otherwise be expected. Table 1 includes a pair of comparisons, between Sea-Tac (SEA) and Olympia (OLM) for western WA, and between Spokane International Airport (GEG) and Felts Field (SFF) for eastern Washington, of minimum temperatures recorded during the last decade (2002-2011). OLM and GEG are about 2-4 °F colder on average in winter than their nearby counterparts of SEA and SFF, and usually about 10 °F colder during extreme events, but probably for different reasons. SEA tends to be warmer than OLM because it is situated on a small bluff. The former location will tend to experience both drainage of the near-surface air that cools most rapidly at night, and greater wind speeds, which serves to mix down warmer air from above the surface layer. The same sort of contrast often occurs in the Everett area; the minimum temperatures recorded at Paine Field (PAE) at 184 m are typically 10-15 °F warmer than those at Arlington (AWO) at 42 m during cold snaps. On the other hand, GEG is both cooler, and at a higher elevation, than SFF and so the same mechanism does not seem to be operating there. A detailed investigation would be required to confirm this, but we suspect the relative warmth of SFF can be attributed to a combination of it being in a more urban environment and near the Spokane River. These effects are not as prominent at GEG, which is located on an elevated plain well southwest of the city center. No matter the cause, this example for the Spokane area illustrates that elevation is not the only determinant of our state’s microclimates.

So how can someone determine if they live in a cold or warm spot? It is easy enough to measure temperatures on one’s own property; a cheap garden thermometer (sometimes even available at dollar stores!) is accurate enough for this purpose. The keys here are to site the thermometer properly, that is with good exposure, and to compare temperatures with those from nearby official weather stations near daybreak during calm, clear and cold weather when local effects can be particularly evident. For readers of this newsletter, we expect that these comparisons will not just be valuable in making the best use of the USDA map towards selection of plants for the yard, but interesting in their own right.