By Guillaume Mauger

We recently held our annual Water Year 2024 Recap & 2025 Outlook Meeting. As a refresher, we often look at our climate through the lens of the “water year”, which goes from October 1st through September 30th, as opposed to the usual calendar year. We do this so that we don’t split our wet season in two.

Focused on Oregon and Washington, our goal in these meetings is to summarize the conditions of the past water year, hear about its impacts (on ecosystems, agriculture, and water supply), and look at what the forecasts say for the coming year. We’ll be releasing an assessment that summarizes all of this in the spring (you can see past assessments here).

In the meantime, we thought it would be helpful to provide a short summary of Washington’s conditions from the last water year here in our newsletter. Overall the water year was warmer than normal (+1.4°F), but only slightly low on precipitation and well within the normal range. Looking by season is where we saw the impacts. In the next few paragraphs I’ll hit on the main events.

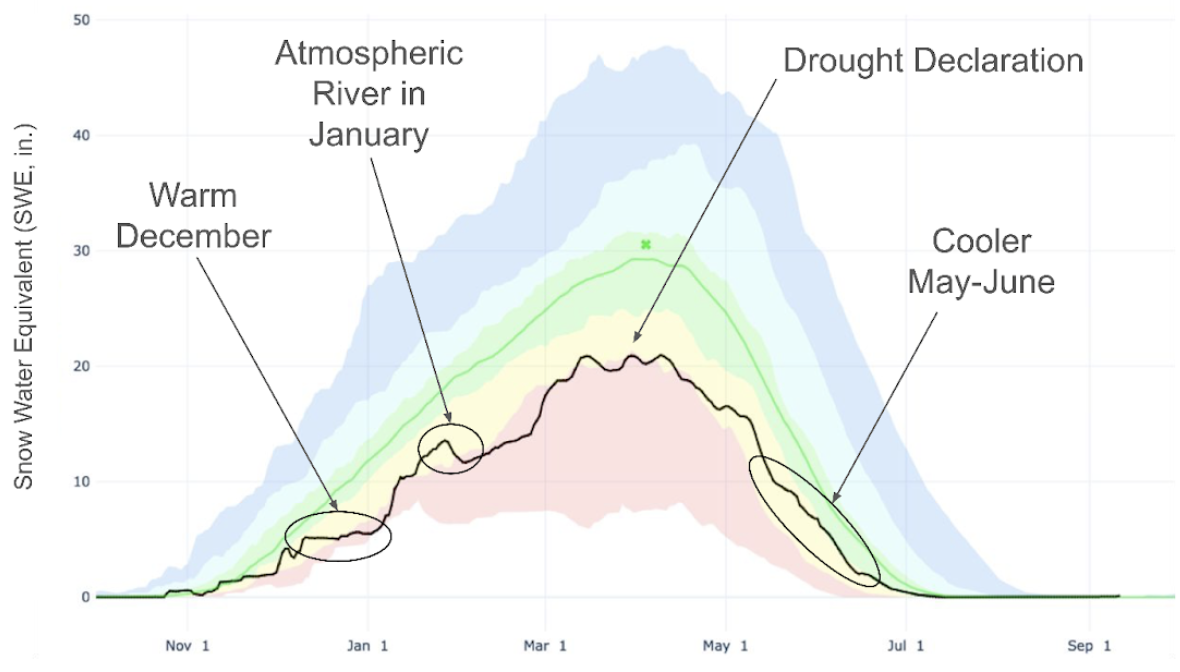

Snowpack was historically low coming out of last winter (Figure 1). A big reason for this was December, which had average temperatures +5.2°F above the 1991-2020 normal, resulting in very little snow accumulation. We also experienced a dip in snowpack when a big atmospheric river hit the west coast in late January through early February. Because they bring air from lower latitudes, atmospheric rivers tend to be warm and often bring rain and melt to higher elevations. As a result of these conditions, the Department of Ecology declared a drought for nearly the entire state of Washington in April.

A secondary reason for the early drought declaration was the seasonal forecasts, which suggested we’d have a relatively warm and dry spring and summer. The spring temperature forecast turned out to be wrong. Importantly, spring temperatures were well below normal for the North Cascades. These mountains hold the bulk of the state’s winter snowpack, so the cooler temperatures helped prolong our snowpack and bring us a bit closer to normal conditions coming out of the spring. Unfortunately, this didn’t help the whole state: temperatures were near normal elsewhere, and precipitation was below normal on the eastern slopes of the Cascades, especially around Yakima County.

By July most of the state’s snowpack is gone, with all but the highest elevations melted out. This means rainfall is key to ensuring there is enough water through the summer season. Unfortunately, this July was anything but that. Statewide, precipitation was only 38% of normal and temperature was +4.0°F above normal (Figure 2). Again, conditions were most severe on the eastern slopes of the Cascades, especially around Yakima County. Not only did this worsen drought conditions, July was when many of our summer’s wildfires flared up. Thankfully, August was wet (more than 150% of normal), and we ended up with a fairly normal fire year. Still, damages and disruptions due to fire were significant, including the Rimrock Retreat fire near Yakima, which prompted evacuations and damaged the Tieton Main Canal, ultimately burning over 45,000 acres.

The Yakima area and surroundings were hardest hit by drought this year. In addition to the damage to the Tieton canal, proratable water users in the nearby Roza and Kittitas irrigation districts received only about half of its usual water allocation. There were major concerns for salmon too, especially given that this was a record year for sockeye returns. On the lower Yakima River, the hot and dry conditions led to record high water temperatures – high enough to be deadly for salmon in some instances, and potentially keep them from spawning in others.

So where are we today, now that we’re heading into winter? As of today, the drought declaration has not yet been lifted. That’s because our fall was unusually dry, with a relatively late start to the rainy season. With the rains we’ve been having this week it might feel odd to say we’re still in drought. But the late start to rains delayed our usual winter build up to normal conditions. Looking forward, we’re hopeful for this winter. It’s looking like a weak La Niña (which tend to be cool and sometimes wet), but those odds are still better than last year’s strong El Niño.

Figure 1: Average Washington Snowpack (black line) for water year 2024. The green line shows the typical conditions (median for 1991-2020), and the shading show the range we’ve seen in the past. The top of the red shading (which tracks closely with 2024 snowpack) is the 10th percentile, meaning that 9 out of 10 years historically have been above that level. Source: https://nwcc-apps.sc.egov.usda.gov/basin-plots/#WA

Figure 1: Average Washington Snowpack (black line) for water year 2024. The green line shows the typical conditions (median for 1991-2020), and the shading show the range we’ve seen in the past. The top of the red shading (which tracks closely with 2024 snowpack) is the 10th percentile, meaning that 9 out of 10 years historically have been above that level. Source: https://nwcc-apps.sc.egov.usda.gov/basin-plots/#WA

Figure 2: Temperature and Precipitation for July 2024, showing warm and dry conditions everywhere, with especially low precipitation on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Maps show the departure from normal conditions, based on the average for 1991-2020, in °F for temperature, percent (%) for precipitation.

Figure 2: Temperature and Precipitation for July 2024, showing warm and dry conditions everywhere, with especially low precipitation on the eastern slopes of the Cascades. Maps show the departure from normal conditions, based on the average for 1991-2020, in °F for temperature, percent (%) for precipitation.