A New Paper Synthesizing Studies on the June 2021 Pacific Northwest Heat Wave Now Available

The June issue of the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society (BAMS) featured a new paper synthesizing over 70 articles on the record-breaking June 2021 Pacific Northwest (PNW) heat wave. I am a co-author on the article, collaborating with experts at Oregon State University and Portland State University. I summarize some of the main takeaways in this piece, and encourage you to check out the article for more details.

Not all heat domes are heat waves and not all heat waves are heat domes – ok, this is more of a personal pet peeve than a take-home from the paper, but I’ll elaborate nonetheless. A heat dome is usually caused by an atmospheric blocking pattern where high pressure aloft inhibits warm air from rising and traps the warm air like a “dome”. This pattern was part of the meteorology of the June 2021 heat wave and the reason it was called a “heat dome”. But not all heat waves are heat domes, and, in fact, the blocking pattern that is usually associated with a high pressure aloft happens more often in winter in the PNW. So unless you know the meteorological mechanisms during a string of extremely high temperatures in the summer, it’s better to just call it a heat wave.

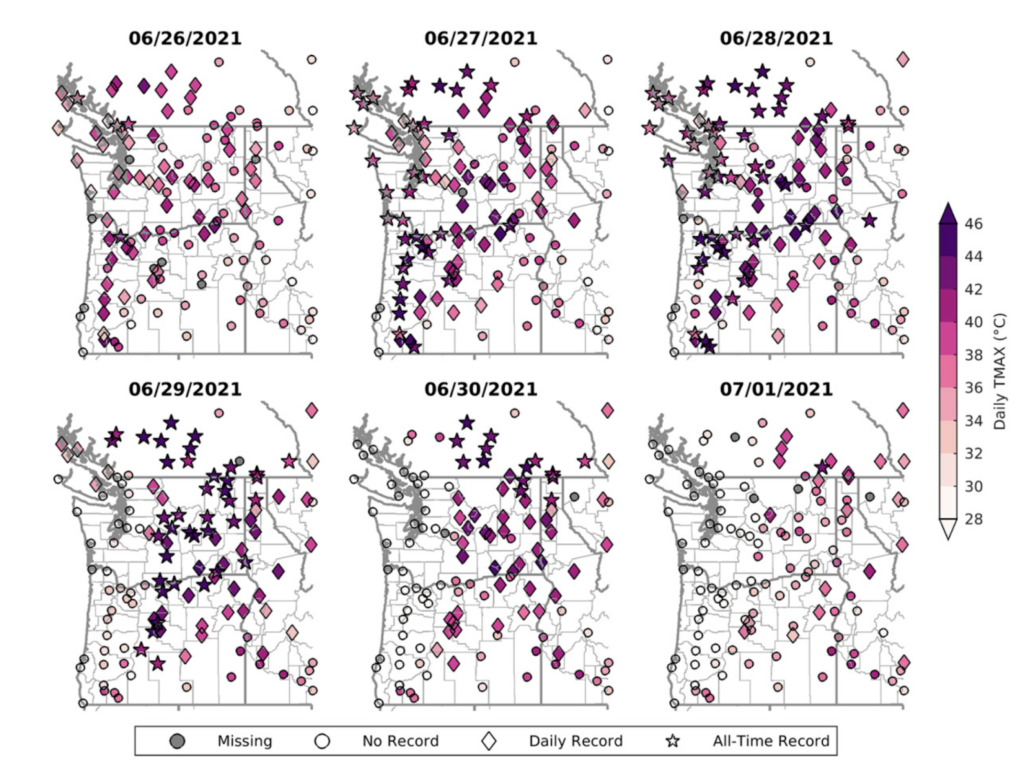

The June 26-July 1, 2021 heat wave was extraordinary across a variety of measures. For example, new analysis was done for this review paper to help visualize the breadth of daily temperature records broken (see excerpted figure). For the 6 days from June 26 through July 1, 52.9% (428 of 809) of the possible daily maximum temperature records and 41.7% (335 of 809) of the possible daily minimum temperature records were tied or broken across British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon. In addition, 156 all-time daily maximum temperature records were tied or broken, including the warmest temperature ever recorded in Oregon (119°F), Washington (120°F), and Canada (121°F).

Climate change made this heat wave slightly warmer and more likely to happen than during the preindustrial climate. As the heat wave was taking place in 2021, scientists and media were already wondering how large of a contribution climate change played into the magnitude of the heatwave. Depending on the methods and exact location of the region examined, the studies reviewed in the paper indicate that between 5 and 20% of the heat wave’s magnitude can be attributed to climate change, which corresponds to between 0.8 and 3.1°C (1.4-5.6°F).

The climate change contribution to the likelihood of the heat wave occurring was more substantial but varied greatly among the studies. For the studies that used historical data, the probability of reaching the temperatures observed during the 2021 heat event ranged from 0.1% to 0.5% per year. This translates into a return period of between 200 and 1,000 years. For this set of studies the likelihood of the 2021 heat wave was at least 340 times higher due to climate change, or couldn’t even have occurred without it.

A different set of studies used climate model simulations to compute the probability of the 2021 heat wave based on a much larger sample size. For these, the 2021 heat wave was estimated to range between a 56- and a 100,000-year event. For this set of studies, the probability of the 2021 heat wave compared to the preindustrial era was at least 8 times higher, and possibly much more.

Regardless of which study is “right”, the heat wave was rare and was made hotter and more likely due to climate change.

Short-term and immediate impacts from the heat wave were widespread. Studies illustrated the impact on public health through increased mortality, heat-induced illness, and the number of visits to emergency rooms. Additional impacts included elevated river temperatures, increased melt of seasonal snowfall and ice, browning or scorch of tree leaves and needles, heat stress in several bird species, and mortality in crustaceans and bivalves in the intertidal zone of the Salish Sea.

This heat wave prompted important climate adaptation planning. This event demonstrated the need for greater climate adaptation measures in response to growing heat risk across the Pacific Northwest. Following this event, Oregon and Washington developed heat guidelines for outdoor workers, and local, county, and state governments created new heat response programs to coordinate long-term planning. The government of British Columbia also developed a provincial heat warning and extreme heat emergency alert and response system.

This is just a preview of the information synthesized in Fleishman et al. (2025). More information can be found in the article and in the references therein.

Reference

Fleishman, E., D.E. Rupp, P.C. Loikith, K.A. Bumbaco, L.W. O’Neill, 2025: Synthesis of Publication on the Anomalous June 2021 Heat Wave in the Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada. BAMS, 106, 6, E1155-E1174.