Winter Preview: What Can We Expect?

As many of our readers are likely well aware, there is a high likelihood (between 60 and 65% chance) of a weak El Niño developing during the fall and winter. Sea-surface temperature anomalies are above normal throughout the equatorial Pacific Ocean at the time of this writing (more information in the Climate Outlook below), but the predicted El Niño has been slow to start. So what does this mean for the fall and winter weather in WA State?

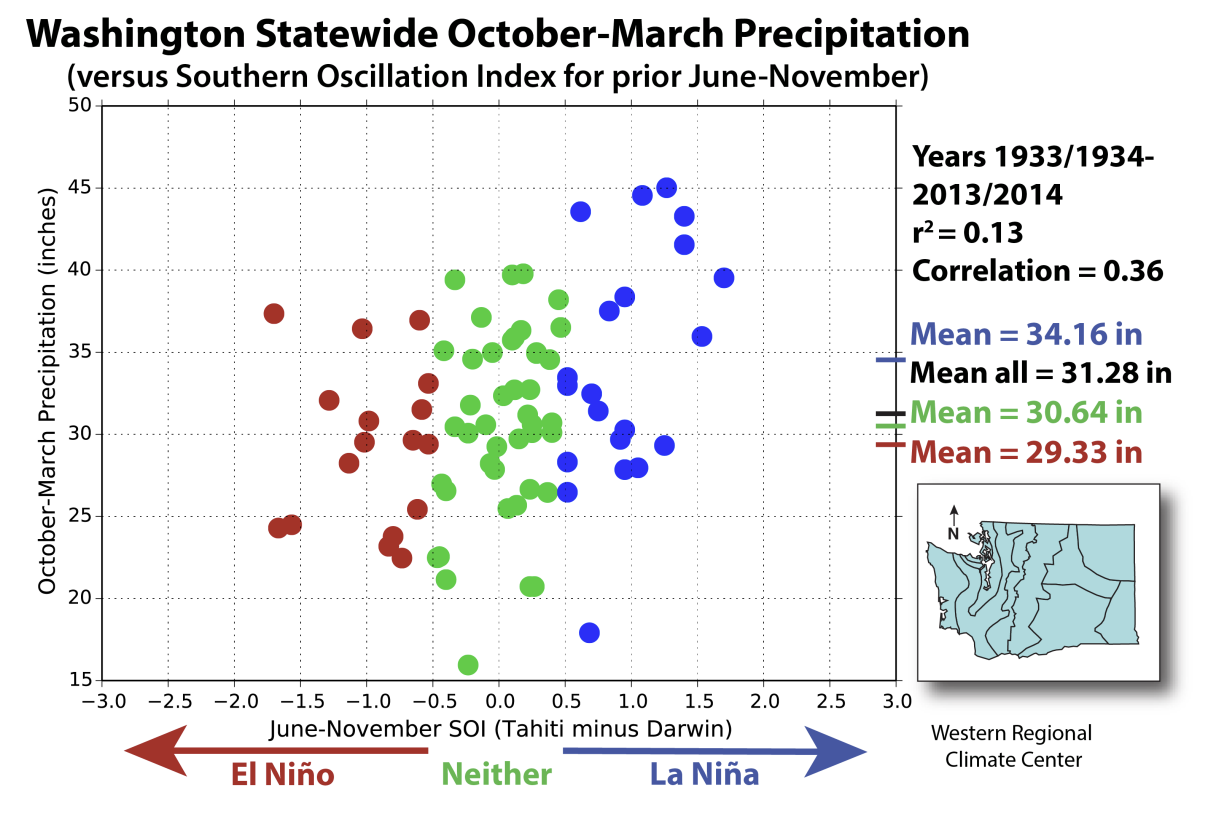

During El Niño winters, there tends to be less total precipitation and snow by April 1 and warmer than normal mean temperatures over the winter as a whole. Figure 1 shows the total October-March precipitation for Washington State compared to the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI) in the preceding months. Negative (positive) SOI indices indicate El Niño (La Niña) conditions; when El Niño conditions are developing or developed, the winter has less total precipitation in the mean statewide. However, it is important to note the variation from one El Niño year to another. While the El Niño winter precipitation mean is about 2” less than the average for all 81 years, there are certainly plenty of El Niño winters that have more precipitation statewide than some La Niña winters. The SOI was only -0.23 for June-August 2014; the tropical Pacific is still considered to be in a neutral rather than El Niño state. But according to the ENSO forecast models as a group, the SOI should continue to get more negative through November.

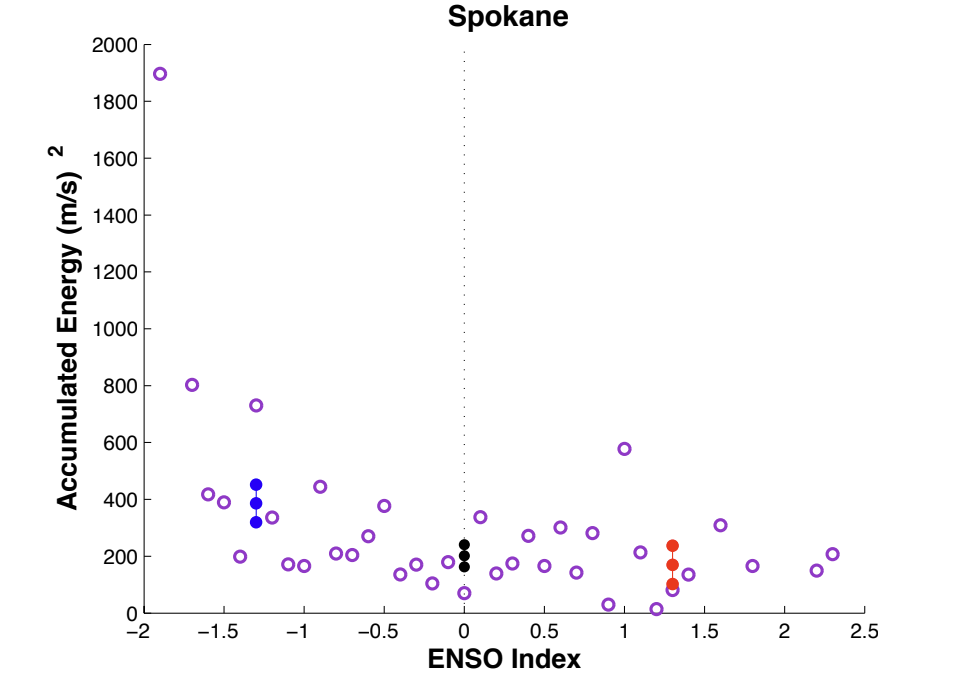

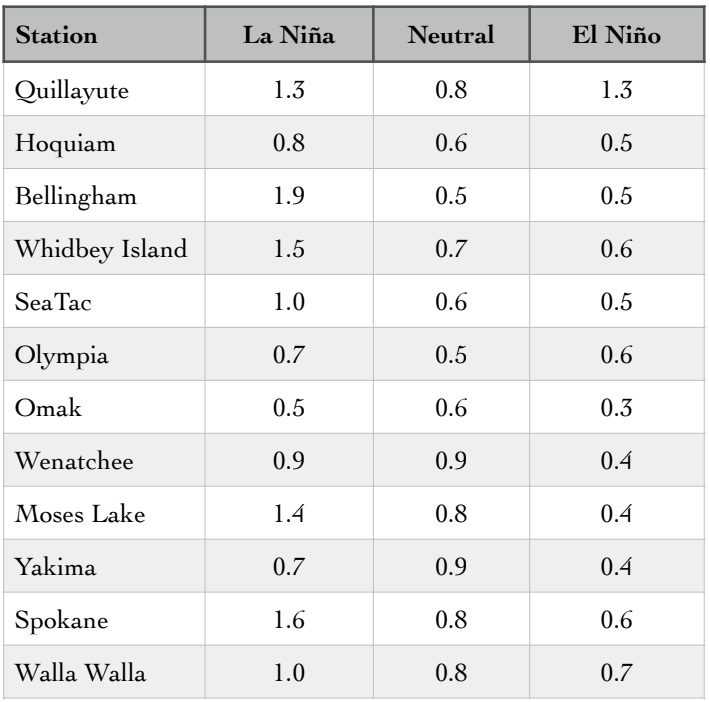

The most recent El Niño was a moderate event in 2009-10. That event provides a good example of how the variability in weather still exists even when the winter mean is predicted as warmer and drier than normal. In early December 2009, an arctic air outbreak occurred causing temperatures in the single digits around the state. Just like lowland snow, those cold air outbreaks are less likely in an El Niño winter but that is not a guarantee that they won’t happen. New research performed by our undergraduate summer intern, Alexandra Caruthers, on ENSO’s influences on WA state windstorms tells a similar story. While strong wind events can certainly occur during an El Niño (such as the Hanukkah Eve Storm in December 2006), there is a lower likelihood of strong windstorms during an El Niño winter (Table 1) for many stations around the state. Figure 2 shows the accumulated energy (AE) of all of the wind events that occurred in each ENSO index for Spokane, and the lines show the mean and uncertainty of the AE for La Niña (blue), neutral (black), and El Niño (red).

phases.

To summarize, the upcoming winter is expected to be warmer and drier as a whole, but there will be variability on a weather event scale just like every other winter. Previous research confirms that lowland snow and windstorms are less likely. Aside from the ENSO forecast, an area of warmer than normal sea-surface temperatures that has persisted in the northern Pacific since last winter – known affectionately as “the blob” – is another sign that a warmer winter than usual is liable to be on the way. The relatively warm temperatures off our coast tend to be reflected in low-level thermal fields over land due to the prevailing winds from the southwest off the ocean.

The factors discussed above are reproduced, at least in principle, by NCEP’s Coupled Forecast System (CFS) global atmosphere-ocean model used for seasonal weather forecasts. The CFS predictions include above normal temperatures and below normal precipitation for a majority of the fall and winter months in WA. Forecasts are available at http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/CFSv2/CFSv2seasonal.shtml.